by Dr Sarah Davey, Research Fellow in the Centre for Sports, Exercise and Life Sciences (CSELS)

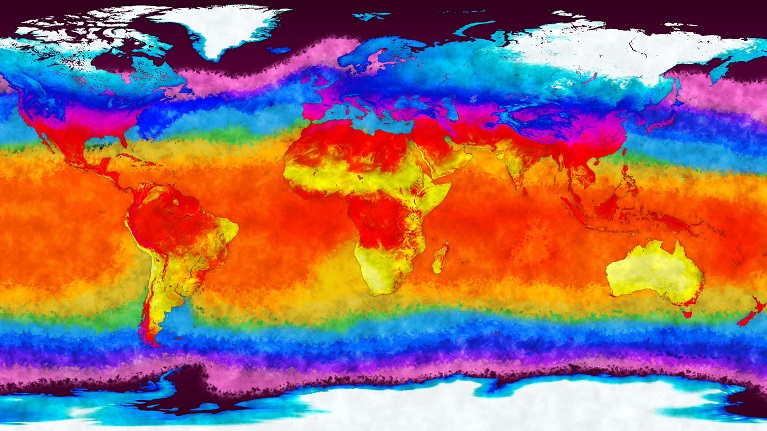

With rising global temperatures and more frequent incidences of heat waves, heat stress has become a worldwide public health issue. Heat stress is when the body is unable to cool down properly causing the body’s core temperature to keep rising to levels that can cause heat-related symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, confusion, headache and dizziness, or in some cases, rise to dangerous levels where key organs can shut down.

Occupational heat stress is termed as heat stress caused by the type of work and/or working environment an employee is exposed to. Occupational heat stress is a concern for both employers and governments Worldwide. For example, it is estimated that approximately 1 million work life-years are to be lost by 2030 due to occupational heat stroke fatalities and 70 million work life-years lost because of reduced labour productivity; causing an estimated accumulated global financial loss of US $2,400 billion by 2030 due to heat stress. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures, especially combined with high-night temperatures that can compromise sleep and recovery, is also a concern for the health and well-being of employees, especially in those who are vulnerable to heat stress and/or its effects. Vulnerable adults include older adults and persons diagnosed with certain medical conditions, namely, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease and diabetes.

The impermeable, encapsulating nature of some personal protective equipment (PPE) impedes heat loss, which, when combined with the extra weight of PPE and restricted mobility, can increase the level of occupational heat stress experienced. Consequently, occupations that require employees to wear PPE have historically been considered to be most at risk of occupational heat stress heat-related illnesses. However, with the estimated rises in global temperatures (range 1.5-4.0 oC) outdoor workers, and workers who work in environments that don’t have (or limited access to) air conditioning, have also been highlighted as populations vulnerable to occupational heat stress.

Occupational Heat Stress within Health Care Facilities

It has been demonstrated that occupational heat stress is an issue for healthcare professionals (HCPs), especially during the summer months or when higher levels of PPE are required (e.g. surgical procedures). Rising global temperatures, are estimated to amplify this issue. For example, during 2019-2020, ~50% of NHS hospital trusts reported incidences of overheating (room temperatures over 26°C), with 8% of trusts reporting over 50 incidents. This figure has been estimated to rise as global temperatures and incidences of heat waves increase. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in the usage and level of PPE required to be worn by HCPs across many roles, further amplifying this issue.

Recent research by the Occupational and Environmental Physiology Group (OEPG) from Coventry University, demonstrated that heat stress associated with wearing the required PPE during the current COVID-19 pandemic can jeopardise the safety, performance and well-being of HCPs with potential consequences for patients. For example, even though most of the HCPs who participated in the research wore the less thermally challenging items of PPE (i.e. plastic apron, surgical face mask, and possible eye protection), they reported experiencing at least three heat-related symptoms whilst wearing PPE, with headache and fatigue being the two most reported symptoms and ~8% reporting episodes of fainting. Related to work performance, ~76% advised that their physical performance had been impaired when PPE was worn. On average, participants also reported at least one cognitive task being adversely affected, with attentional focus being the most frequently reported (92.4%).

Strategies to mitigate heat stress with Health Care Facilities

Several mitigation strategies deemed to be effective in preventing or reducing heat stress in HCPs have been recommended, some of which may not be available to HCPs or they have a reduced access to. The main strategies are listed below

- Reduce length of exposure by taking longer and more breaks

- Take breaks in a cool room

- Take breaks outside in the shade

- Frequently drink cold drinks

- Use cold towels on skin to remove heat

- Immerse hands and/or feet in cool water

- Wear a cooling vest underneath uniform

- Remove PPE more often

- Use electric desk-top type of fan

More Research is required

Even though evidence suggests occupational heat stress could be an issue for HCPs in Health Care Facilities, there is limited evidence available on the incidence and effect of heat stress experienced by HCPs within NHS health care facilities, either associated with or without wearing PPE. In addition, there is also limited information available on whether certain policies produced for employees are effective in mitigating heat stress within the workplace

In response, the Occupational and Environmental Physiology Group (OEPG) has developed an anonymous survey aimed to capture the incidence and effect of heat stress experienced by HCPs in NHS health care settings. The survey is also designed to capture how HCPs manage or mitigate heat stress in their working environment. The end objective of the survey is to better understand and characterise the incidence of heat stress amongst HCPs and subsequently, if required, to inform policy to help mitigate occupational heat stress with NHS settings to improve HCPs’ working life and well-being. Additional research is being conducted to better understand the effect of occupational heat stress on HCPs’ clinical performance and chronic exposure to heat stress on HCPs’ health and well-being.

If you are a HCP working in the NHS and would like to share your experience of heat stress at work then please use the link below to complete the anonymous survey. The anonymous survey should take 10-20 minutes to complete.

Heat stress within the workplace – NHS.

If you would like any further information about the research being undertaken by the research team on this topic, or are interested in partaking in any further research, please contact Dr. Sarah Davey.

Recent publication

Davey, S.L., Lee, B.J., Robbins, T. Randeva, H. Thake, C.D. (2021) Heat stress and PPE during COVID-19: impact on healthcare workers’ performance, safety and well-being in NHS settings. Journal of Hospital Infection. 108:185 – 188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.027

Comments are disabled