Why do so Many Americans Claim Indigenous Heritage – The Complex History of America’s Racial Politics [Darren Reid, History]

Originally published in The Conversation October 31 2018

Elizabeth Warren, the Democrat senator and Trump critic with an eye on the White House, and Cesar Sayoc, the man accused of mailing pipe bombs to the Clintons (among others), have at least one thing in common. Both claim some type of Native American identity. Warren even released results of a DNA test which appear to show the existence of a Native American ancestor six to ten generations removed – although some have found the results problematic.

But despite the high-profile nature of these cases, Warren and Soyac are far from unique. The claiming of Native American heritage has long been an important, if little discussed, aspect of US culture.

When Johnny Depp accepted the role of Tonto in 2013’s Lone Ranger reboot, he had in the past claimed possible Native American heritage, believing that, “my great-grandmother was quite a bit of Native American, she grew up Cherokee or maybe Creek Indian”. Around the same time, however, Ancestry.com surveyed Depp’s family treeand didn’t find evidence of Native American ancestry. It did, however, discover that Depp had African American ancestors.

Read more: Two Native American geneticists interpret Elizabeth Warren’s DNA test

At some point in the past, it is possible that one of Depp’s maternal ancestors began passing for a Native American: that is, they assumed a new ethnic identity which would have helped shield them from the worst types of discrimination directed towards Black Americans. Native Americans may still have been treated poorly, but many people of mixed racial descent did likewise.

The American Indian “fantasy” has changed significantly over the past three centuries. At different points in time, Native Americans have been vilified; celebrated as noble savages; held up as paragons of environmental sensitivity; and depicted as custodians of spiritual truths. Often, they are celebrated as several of these things simultaneously, the precise combination reflecting the current needs of the dominant, settler-colonial culture.

In the 19th century, for example, Native Americans were frequently depicted as the natural enemies of American civilisation, an image which encouraged and justified the genocidewhich occurred during this period. As the military threat posed by Native Americans declined, however, other aspects of the settler-colonial “fantasy” took hold.

Grey Owl

Certainly many people appropriated Native American heritage. In the early 20th century, Englishman Archibald Belaney migrated to Canada where he styled himself as Grey Owl, a “Native American” who made it his life’s mission to teach White Americans the value of environmental conservationism. His true identity was only revealed after his death.

In the 1930s, meanwhile, Espera Oscar de Corti, who was born to a pair of Italian émigrés in Louisiana, changed his name to Iron Eyes Cody and assumed a Native American identity which exploited his physical resemblance to the period’s stereotypical Native American “look”. In 1971, Cody found immortality as the “crying Indian” in the iconic Keep America Beautiful conservation campaign.

Sylvester Long

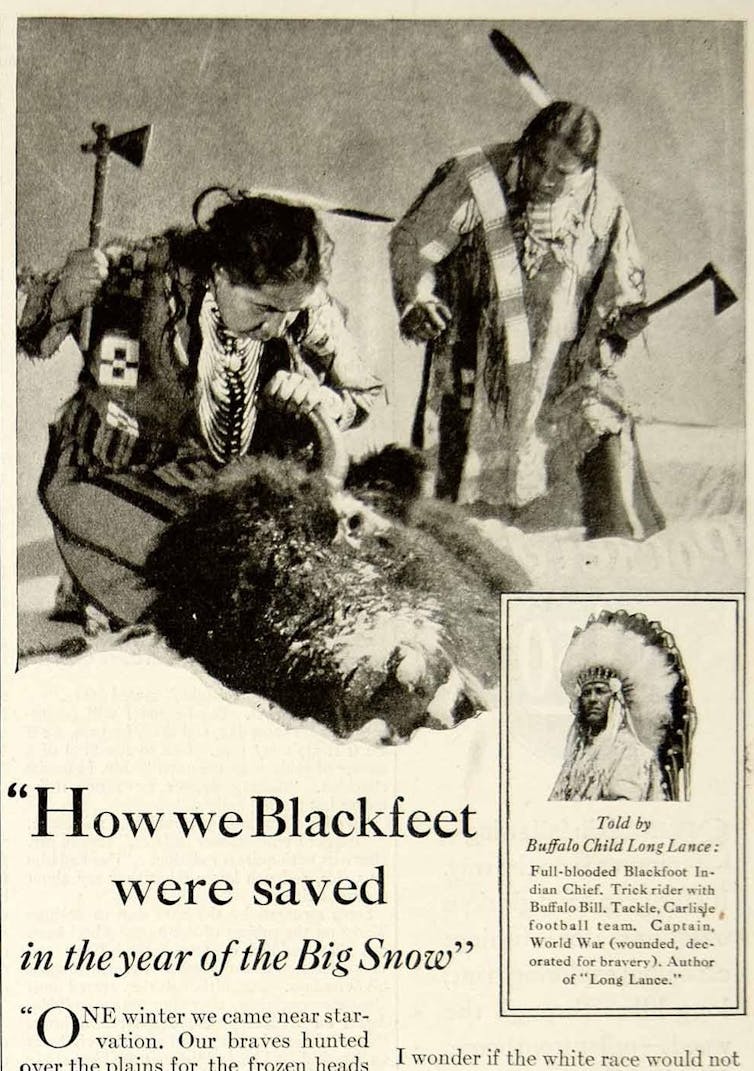

Other cases are more complex. In the 1920s, Sylvester Long, whose mixed racial heritage appears to have included white, African American, and Native American elements, adopted a fabricated Blackfoot identity. Unlike Cody and Belaney, Long was part Native American, but he discovered that his eastern native Croatan heritage was of less interest to white Americans than the romanticised imagery which surrounded the native peoples of the far west.

Responding to this, Long remade himself into the son of a Blackfoot chief, becoming Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance. This new identity allowed him to avoid the worst anti-Black prejudice of the period. Indeed, it made him the toast of the New York party scene, where he found validation, adulation, sex – and a publishing deal for his (fictional) autobiography. Predicting Cody’s later career, Long starred in the 1929 film The Silent Enemy. In 1932, after the nature of his Blackfoot identity was exposed, Long killed himself.

Native Americans continued to face punishing levels of discrimination throughout the 20th century even as white Americans imagined new, fantastical versions of them. They became the ideal vehicle into which Americans could fold many of their anxieties about modernity and industrialisation. As a result, the imagined Indian, which was largely the creation of white America, became an object of increased admiration and fetishisation.

Warren’s DNA test suggests she does have a Native American ancestor. But, as her critics point out, DNA is not the same as lived experience. Indeed, her desire to prove a link to Native America says much about the ongoing processes of cultural colonisation which are occurring in the US.

Native American identities have been co-opted throughout American history, and they remain valuable commodities. Indeed, even in the 21st century, the colonisation of Native America continues through appropriation, even if the colonisers are oblivious to the context and consequences which surround their claims to an aboriginal identity.