Guest post by Dr Andrew Perchard, Centre for Business in Society

The latest announcement by Tata Steel of the loss of a further 1200 jobs in the UK steel industry – 970 in Scunthorpe, North Lincolnshire, and 270 in Lanarkshire, Scotland – has highlighted both the divergent approaches of the UK and devolved Scottish governments to this issue, and also opens old wounds of the legacies and memories of previous closures. These closures follow on announcements of job losses in steel at Tata’s plants in South Wales and South Yorkshire, and Thai producer SSI’s Redcar works. While the Scottish Government made a virtue of its proactive stance in immediately announcing the setting up of a taskforce, and an immediate search for possible new owners, the UK government came under considerable criticism for its initial deflection of responsibility, blaming global markets and professing powerlessness to act.

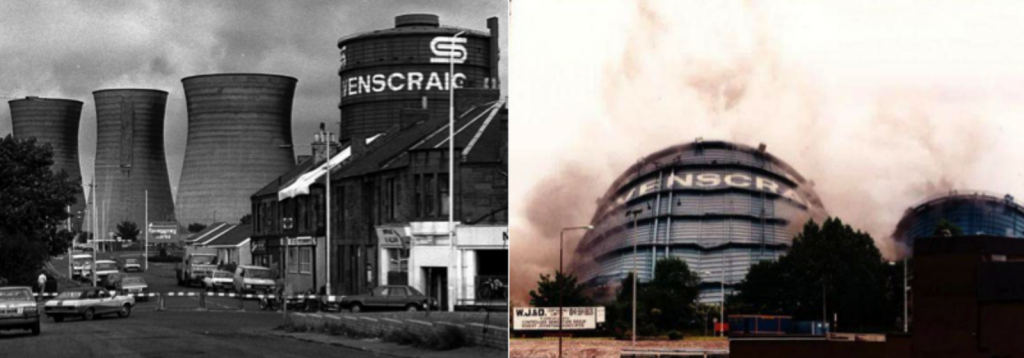

This latest round of closures is a sharp reminder of the legacy of industrial closures across the UK. The UK, like other parts of Western Europe (such as the Ruhr Valley in Germany and Lorraine in France), and North America’s “Rust Belt”, has experienced contraction in its industrial heartlands since the late 1960s. Commentary by policymakers and economists has tended to talk about this in terms of job loss figures, and the transformation of the economy from manual jobs to the service sector. In a pathbreaking study of industrial contraction in the Austrian textile town of Mariethal in 1938, social scientists Marie Johoda, Paul Lazarsfeld, and Hans Zeisel noted: “When we try to formulate more exactly the psychological effects of unemployment, we lose the full, poignant, emotional feeling that this word brings to people.” With the end of the “golden years” of economic growth (1950 to 1973), and with it the mirage of permanence of industrial employment, closures left “survivors”, as American historian Hank Greenspan has put it, “confronting a sense of being disposable en masse”. As one of a number of researchers looking “beyond the body counts” of industrial closures at the long term cultural, as well as social and economic effects, of deindustrialisation, I argue that policymakers need to recognise the full implications of these closures. Some measure of the long term effects of such closures can be seen from the range of legacies of industrial closures across a number of parts of the UK, with the most striking examples, in terms of multiple deprivations, evident in former coalfield areas in England and Wales and Scotland. More broadly, the cultural impacts of deindustrialisation are to be seen in shifting political allegiances and profound national soul-searching. As the seasoned political journalist, Neal Acherson, observed of Scotland in 2003: “Scotland’s industrial landscape… became archaeology… These ways of working had long ago become part of Scotland’s self-definition. Now a third identity-question was added to “When was Scotland?” and “Who are we?” It was: “What do Scots do?”’. As I have written elsewhere, the legacy of deindustrialisation features prominently in Scottish national consciousness and helps to explain political change in Scotland and growing support for independence. The legacy of deindustrialisation in Scotland was symbolised by the fact that both the Scottish Conservatives and Scottish Labour Party used the site of the former British Steel Ravenscraig stripmill (closed in 1992) to launch their General Election and Scottish Parliamentary Election campaigns; the Conservatives to underline the transformation of the area into a business park signifying new enterprise culture, and Labour to remind Scottish voters of the legacy of Conservative rule in Scotland. The bulk of the jobs to go in Scotland are at Dalzell Steel and Iron Works in Motherwell, close to the old Ravenscraig site, the others in Cambuslang, a former coal mining area.

Ravenscraig has become a powerful symbol in Scotland’s national narrative, featuring in song and literature. Ravenscraig was testament both to the failures of postwar government regional planning and to the commitment of Conservative governments between 1979 and 1997 not to support “white elephants”. The cultural manifestation of a groundswell of anger within deindustrialised communities has been evident on both sides of the Atlantic, seen in the canon of work of artists like Bruce Springsteen, informed by his own life experiences and from reading accounts of closure in the Steeltown USA, Youngstown, Ohio. That community anger was voiced by activist-historian Staughton Lynd, in his reflections on the closures at Youngstown: “Why may a corporation unilaterally decide to destroy the livelihood of an entire community? Why should it be allowed to come into a community, dirty its air, foul its water, make use of the energies of its young people for generations, and then throw the place away like an orange peel and walk off?”

In the weeks ahead policymakers – both at Westminster and Holyrood – will need to reflect carefully on the long term legacies of deindustrialisation in formulating their responses.

Dr Andrew Perchard is Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Business in Society. He has written widely on industrial history, deindustrialisation, and is co-editing the forthcoming collection (with Steven High and Lachlan MacKinnon), Deindustrialization and its Aftermath with University of British Columbia Press.

Comments are disabled