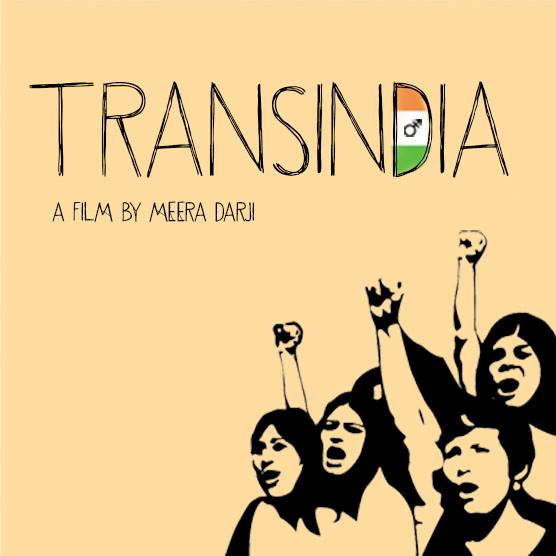

Meera Darji is a third-year Media Production student. For her final project Meera has produced a unique documentary on the subject of Hijras; the transgender community in India. Her film will be screened during the #covdegreeshow 2015.

A Hijra is (in India) a person who adopts a gender role that is neither male nor female. Meera’s documentary, TransIndia, aims to take you on a discovery of the real Hijras, exploring their history and lifestyle. Meera also questions how attitudes towards India’s once esteemed third gender have changed so dramatically that they are now often ostracised and rejected from society.

What inspired you to create a film about Hijras?

In my final year of University, we were asked to research the history of sex in different countries. I found that in Hinduism sex used to be seen as a desire one must explore to achieve Karma. However, sex is currently considered a taboo subject in India, and it is a sin to commit; one must be celibate till marriage. I wanted to know why the values and perceptions of sex had so drastically changed in India, and why it has become such a prudish society.

My research led me to discover that there are many other ‘taboo’ issues creating conflict in India. For instance, the notions of sexism in India and how various sexualities were either against the law or hardly spoken about. The Hijras of India immediately fascinated me; I was awed by their appearance. Through thorough research and contextual analysis, I discovered their importance in the pre-colonial century and the sudden shift in their hierarchy position. I was fascinated by the fact that they were effectively ostracised by society.

Why did opinions of Hijras change so quickly?

The ostracism began when the British colonised India and introduced the 1871 Criminal Tribes Act which criminalised all Hijras. They were labeled them as immoral and corrupt. Hijras were very much accepted in society before this Act; they even resided with the King and Queen as protectors of the land! They have also appeared in ancient Hindu scriptures. However, when the British Raj adopted these new rules, the whole community was eventually stigmatised.

Through intensive research on the Hijras, I found there were many misconceptions of their communities and these seemed to have shaped the perceptions that society had of them. Many of the stereotypes were negative. They were falsely blamed for kidnapping children, their ceremonies were seen to bring bad luck, they were accused of forcing young boys to castrate and the most common misconception was that they were ‘just men dressed in saris’. The majority of these stereotypes were reinforced through dramatized Indian soaps and films, which portrayed Hijras as antagonists, masculine, forceful and evil.

How do Hijras live in India, can they be open about their gender-choice or do they still live in seclusion?

Hijras live in their communities. They usually travel together to beg on the streets and visit marriages and birth ceremonies, where they bless the families for luck and fertility and are given money in return. All the Hijras are open about their gender-choice at a young age, yet they often struggle with bullying and being neglected from society. Even their families find it difficult to accept them, so it is likely that they will leave their families and join the Hijra community. In some cases, as seen in TransIndia, parents can gradually come around to the idea of their child being transgender and are seen to strongly support them.

Do trans-operations happen in India?

Trans-operations do happen in India, yet not in the average hospital-doctor way. It is vastly different. Previously, hospitals in India would not touch a transgender person or conduct any operation on them. The laws have changed now; doctors must treat all their patients fairly. However, communities tend to do the sex-change operation on their own. A huge part of the Hijra religious process is the ceremony of the Hijra removing its masculinity through castration and becoming female. As my film explores, the Hijras undergo castration in their communities using no anaesthetic and only a heated metal rod. Indeed, the process is painful, yet they believe it shows their true identity as a Hijra and connects them with the Mother Goddess.

Was it hard to convince people to take part in your documentary, were they worried about being exposed?

As I had family in India, I managed to find my subjects around various cities in Gujarat. At first they were quite wary of my intentions and the purpose of the film. However, once I explained the notions behind it, they were quite happy to be filmed. Pre-production started quite early, so I had the opportunity to develop and build a rapport with my subjects, so I gained their trust. I wanted to regularly communicate with them, to show my appreciation, but also my passion and seriousness in wanting to gain a true insight in their lives. It was also crucial to me that I was capturing the truth, rather than reconstructing reality. By gaining that element of trust, I found that my subjects shared a lot of their daily struggles and personal lives to the camera.

Do you believe the attitude towards transgender individuals has changed in modern society, both in India and England?

Despite these new laws being established by the British Raj, England has since moved on; gender identity is more acknowledged here and support is provided without prejudice. Through the research and making of the film, I have learnt that respect differs in different cities in India. In the majority of places ostracism still remains, yet in some, gradual change is taking place. Change is happening, but very precariously, and I think it needs to be done faster, before the whole country drowns in the misconceptions.

What do you hope to achieve with your documentary?

With Transindia, my aim is to not simply show the Hijra’s struggle in society, but to perpetuate the fact that they are humans too. People need to start accepting them and be rid of the prudish abstract which surrounds their gender identity. They have different sets of traditions and cultures, but they also have a voice. They belong to a tight-knit community and are trying to make ends meet with what they have. I wanted to give my audience an insight into their true lifestyles.

Transindia will be exclusively screened at the 2015 Coventry University Degree Show tomorrow, 30th May, at 2pm along with additional great films by students. Please come along to Graham Sutherland, GS22 and witness the first viewing of all the #covdegreeshow films!

unCOVered also interviewed Meera about her media production course, find out more here. You can support her film by joining the TransIndia Facebook page or following the TransIndia Twitter! You can also follow Meera on Facebook and Twitter.