Shutterstock

Guest post by Dr. Emma Vardy, Centre for Advances in Behavioural Science

It’s always a joy on World Book Day to see the Harry Potters, Alice in Wonderlands and BFGs filing through the school gates. The more cynical among us may wonder – after seeing the 20th Harry Potter heading to the playground – if these children have actually read these books or only watched the films, or if their outfit was the only costume available. But World Book Day is an important date to celebrate books, promote a love of reading and to support children to see that reading isn’t just a school thing.

Until recently the focus, both in schools and in the field of reading research, was on how children learn to read and how to get youngsters to read at their expected age level. But there is now a greater emphasis on the enjoyment of reading. Personally I love to read, picking up a book, whether it be deemed for an adult, young adult or children, offers escapism as well as a chance to learn. But for some children reading can be a struggle and seen as a chore.

Affective factors – an umbrella term for constructs such as motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, self-concept and confidence – offer a different lens to look at reading development.

If a child struggles to read, they may hold a negative attitude towards reading and be less motivated. They may only pick up a book for extrinsic reasons, such as to earn a reward or to avoid punishment. Ultimately, they may be disengaged from reading.

Improving affective factors such as attitude, motivation or confidence can engage children with reading more, leading to improved reading ability. Reading for pleasure relates to the idea of reading for intrinsically-motivated purposes – thus a child reads because they value reading, enjoy reading and see it as worthwhile. This can have a number of benefits – including supporting reading attainment and writing ability, helping with comprehension skills and grammar, extending vocabulary and developing self-confidence and a positive reading attitude as well as wider benefits such as understanding different cultures (Clark & Rumbold, 2006).

Yet, children in England were reported to read less for pleasure compared to other countries (Twist et al., 2007). And furthermore, while reading achievement may increase from ages 8 to 12, reading enjoyment and reading self-efficacy declines (Smith, Smith, Gilmore & Jameson, 2012).

But there are several things that schools can do to help engage children with reading for pleasure.

- Choice: Children need to have choice over their reading material. Research has shown that youngsters enjoy reading books when they have selected them themselves (Gambrell, 1996)

- Access: They need access to an array of reading material, – fiction and non-fiction, comics, graphic novels, newspapers, magazines etc. All these count!

- ‘Proper Reading’: A theme of our research has been the idea of proper reading; that children have been told they cannot read a comic or a graphic novel, or Diary of a Wimpy Kid, because these are not ‘proper reading’. But for a child who struggles with reading, these are ideal. They have limited words, include pictures, are not intimidating and can be a gentle way into reading. This can motivate children to challenge themselves, and develop their confidence as reader.

- Good reader: School’s should challenge the idea of what a good reader is. Self-concept is individual’s perception of themselves- in this case whether they think they are a good reader. This perception is formed by teacher feedback, observations and peer comparisons. Our research shows that children mainly focus on test scores and reading schemes to describe what a good reader is. But couldn’t a good reader just be someone who likes reading or someone who can name a lot of authors or books? We should challenge this idea that a good reader is related only to reading ability. That is just too much of a narrow focus.

- Recognise ‘outside school reading’: Research has shown that adolescents are more likely to read outside of school, when they feel their teachers value this. Teachers should allocate time in the classroom to discuss what everyone has been reading away from their lessons, in order to value outside school reading.

- Book clubs: Book clubs that focus on engaging children with reading and not improving reading ability have been shown to increase reading motivation, attitudes towards reading and the amount of reading. My favourite quote from our evaluation of Chatterbooks – a national book club scheme by The Reading Agency – was ‘Miss tricked us into reading’. The children loved the games, fun activities and reading was incorporated into the sessions. We have a pack for schools that can be e-mailed for free on how to set up a book club with all the materials needed for the 10 weeks. If you would like this for your school e-mail Dr Emma Vardy vardy@coventry.ac.uk

Each time a child tells me that they don’t like reading, I think it’s just that they haven’t yet found the right book, comic or other reading material that interests them.

The key to helping children who struggle with reading, or are considered disengaged, is to not just focus on the cognitive processes of reading. Teachers and parents need to take the time to look at the affective factors that play a part. What’s needed to create lifelong readers is an intervention that improves reading achievement and affective factors.

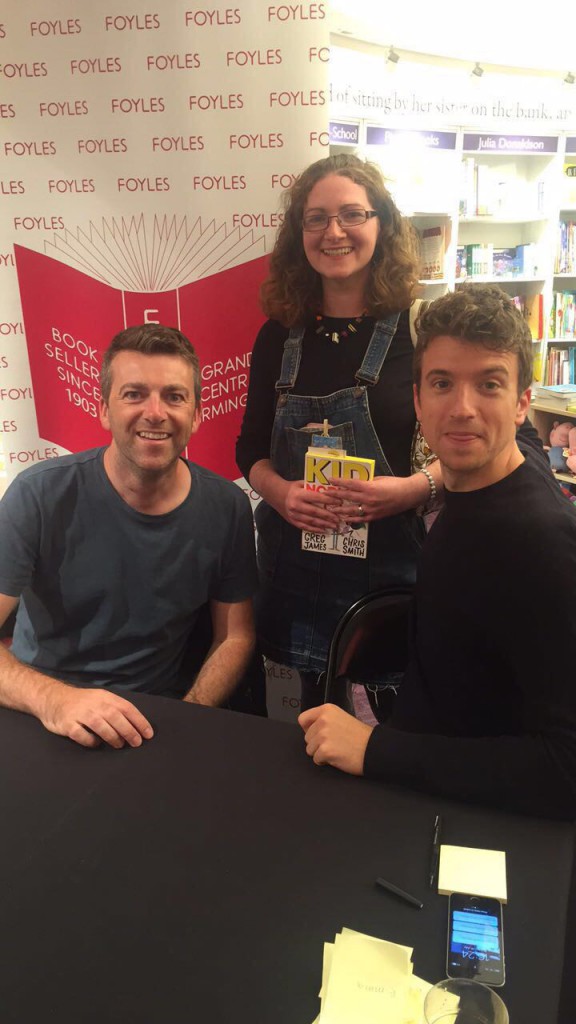

Dr Emma Vardy is a Research Associate in the Literacy Team at Coventry University. Emma’s research focuses on how affective factors influence literacy development. She has recently completed a piece of research evaluating the impact of a Read2Dogs scheme, and has evaluated interventions such as Chatterbooks that aim to improve children’s reading for pleasure. Emma is a big book nerd, and can be found at author events like the one in the photograph.

Comments are disabled