Britain’s first social supermarket: Community Shop in Goldthorpe, Yorkshire. Lynne Cameron/PA Archive

Guest post by Dr. Lopamudra Saxena, Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience

Social supermarkets have emerged in Britain in the past five years as a response to food poverty and food waste. These non-charitable initiatives sell food “surplus” to people on low incomes at heavily discounted prices, and provide social support.

In new research, my colleague and I have mapped the growth of social supermarkets and found that while they help support people who are struggling, they do little to challenge the inequalities in the food system.

Despite being the fifth richest country in the world, food poverty in Britain has increased over the last decade. Based on UN estimates, as many as 8.4m people are food insecure in the UK. Meanwhile, there has been intense media and political attention on the amount of food that goes to waste in Britain. It is estimated that around 10m tonnes of food is wastedonce it has left the farm gate in the UK every year. This waste is generated at various points in the food supply chain by producers, wholesalers, retailers and consumers.

It’s within this wider context of austerity conditions: rising food poverty, rising food prices, welfare reforms and budget cuts – alongside policies to try and redistribute food surplus – that social supermarkets emerged.

What makes a social supermarket

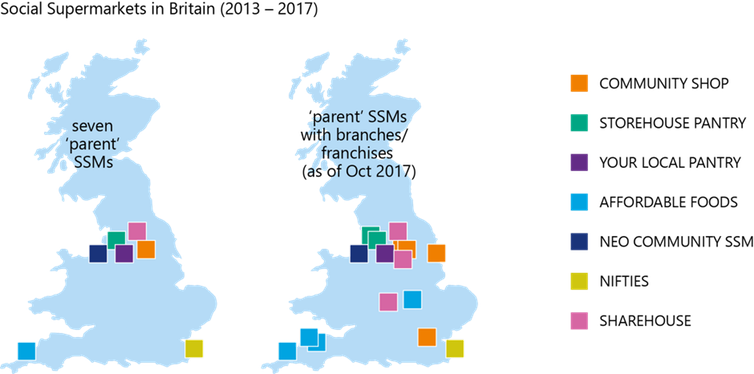

The first social supermarket was launched in 2013 in Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire. By October 2017, our study had identified seven “parent” initiatives, each with several branches or franchises, which describe themselves as social supermarkets or have one of three key features.

First, they primarily stock food surplus, as well as some non-food goods. These are products originally intended for sale in the mainstream market which have become unsaleable. These include products which are very close to or past their sell by or best before dates, those with damaged or old packaging, discontinued products or mislabelled goods with spelling errors or wrongly advertised weight. They can also include excess stock from supply errors or sudden changes in customer demand as a result of changes in weather, stock left over from promotional offers or marketing roadshows, and also blemished fruit and vegetables.

Food isn’t given away for free or handed out, as in food banks. Instead it’s offered in a retail-like environment at heavily discounted prices – in some cases up to 70% off supermarket prices. Access is generally on a controlled basis to “members”, selected by using certain socioeconomic or geographic criteria, to target those who are at risk of food poverty and need support. In some, access is open.

Second, social supermarkets offer wraparound services to their members. These could be formal support programmes, such as skills development, training, debt and welfare advice, or informal support which aims to reconnect people with food, build relationships and break barriers. For example, there is a Community Kitchen at Community Shop offering a “social eating space”, in which people come together and build very strong relationships around food. The Storehouse Pantry in Bolton has a “market place” where members are offered wraparound support on various issues such as indebtedness, overcoming addiction, gaining employment skills and cooking.

Third, social supermarkets are all social enterprises with multiple goals. They have an economic goal to sell or provide access to low-cost food which enables their users to save money, and a social goal to support those who need help the most. And they have an environmental goal to reduce food waste by facilitating the redistribution of food surplus.

The social supermarkets we located were particularly in areas lying within the 10-20% most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK. Each of them has further plans for expansion and many more social supermarkets are also in the pipeline.

The growth of social supermarkets in Britain.

Each of these social supermarkets is organised differently. They vary in where they get the food surplus from, the type and range of food they stock and the prices, the type of access, and the nature and extent of social support they provide. The number of members or users in the controlled access social supermarkets range from as high as 750 in each of the four stores of Community Shop to around 60-70 in each of the two locations of Storehouse Pantry in Bolton.

Risk of becoming part of the broken food system

Social supermarkets have emerged to fill a gap in austerity Britain by providing a social safety net. In the short-term, these initiatives provide a degree of choice and dignity to those people who are food insecure, helping them to save money, gain skills and confidence. They are a step beyond food banks and help in mitigating the effects of poverty and social vulnerability. Their impact on the increasing numbers of people turning to them cannot be underestimated.

However, social supermarkets are also vulnerable. Risks to their survival arise from the complexity and unpredictability of food surplus supply links, a heavy reliance on volunteers in some cases, and their financial viability. This raises questions about their sustainability and the positive outcomes they expect to achieve in supporting vulnerable people.

If social supermarkets become normalised, that may delay the solution to some of the deep structural problems in the British food system and economy which such initiatives emerged as a response to. Their vision is to reduce food waste, but they rely on a regular and a continuous supply of food surplus which undercuts the prevention of food waste as a priority. Their social mission is to support people out of food poverty, but they work closely within a market system and a food industry which has faced criticism for creating greater inequalities through low-wage work.

Their ability to provide healthy nutritious food is variable and often limited. In many cases, there are few questions being asked by social supermarkets about the issues associated with providing cheap food that is highly processed and nutrient-deficient – and the impact this has on existing health inequalities in the communities they serve.

So, while these bottom-up approaches offer important opportunities to help society’s most vulnerable, it is vital to reflect critically on their place within the context of transformative solutions which are needed to tackle the root causes of food poverty and food waste in the long term.

Originally written for ‘the Conversation’.

Comments are disabled