by Jackie Abell

With sharp declines in wild lion populations throughout Africa within a short period of time, conservationists are engaged in a suite of strategies to protect and increase their numbers in the wild. Here at the African Lion and Environmental Research Trust, captive lions are given opportunities to develop their natural hunting instincts, to live as socially stable prides’ and to sustain themselves in a wild environment. With skills comparable to wild lions, these captive born lions can raise their own offspring without any interference from humans. It is this second-generation of ‘wild’ lions, born of captive-parents’, that are candidates for release into those areas of Africa where wild populations have declined. Research therefore has two broad elements. The first is to assess and monitor the behavioural development and ecology of captive and wild-born lions. The second is to address those factors that have led to the decimation of wild populations and to ensure the protection of lions in the future. As the human population booms, lions find themselves in increasing conflict with them for space and food. Lions rarely win these conflicts. Conservation research therefore, must be multi-disciplinary. Over the next 6 months, I’ll give you an insight into the research we’re doing out here to protect and restore the African lion, and benefit the lives of their human neighbours.

May has been about cubs! Little is written about the development of play behaviour in this highly social predator. When do they begin to play? What different types of play behaviour do they display? Are there changes in the frequency and type of play behaviour as lions develop with age? Do male cubs play differently to female cubs? And what is the purpose of this energy-costly behaviour? We’ve been observing cubs aged from 2 months to 18 months of age, to find out. Data collected over a period of 4 years shows that play behaviour changes in quantity and type with age, and there is a difference between male and female cubs in the behaviours they express. This makes sense if we consider play behaviour to be ‘safe practice’ of those skills lions will need as adults. Wrestling, stalking, chasing, biting, and running are all activities lions require to survive. As adults, males will be fighting other males for tenure of a pride, and territorial defence. Adult females will almost certainly be doing the lions’ share of the hunting, and the pride will depend on their success. This sex differentiation seems to be reflected in the types of play behaviours our cubs are displaying from an early age. I’m currently finishing writing two papers to contribute to a sparse field on play behaviour in lions.

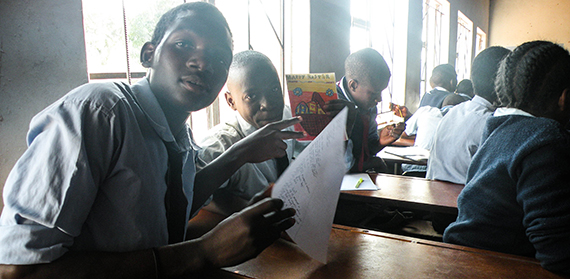

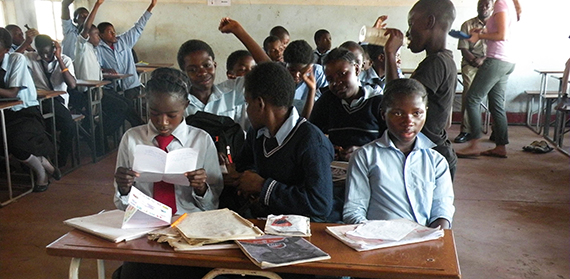

Next month, researchers from Coventry University’s PSI-CAB research centre are in Livingstone to implement a conservation education intervention we’ve designed with local schools. The aim is to foster positive attitudes and behaviours to wildlife generally and lions in particular. I’ll tell you more about this next month. I’ll leave you with some photographs of our playful cubs, and also children from our conservation education class at Mukamusaba School in Livingstone. These children have just received their latest letters from their pen-pals at Chesham County Primary School in the UK, and have swapped hand-drawn posters about litter pollution. I’ve twinned these two classes so they can learn about conservation together.

These are our conservationists of the future!

Comments are disabled