When it comes to the thorny issue of Islamisation in Turkey, most external commentators focus on whether Turkey is becoming more Islamic in its governance, and what this would mean for Western interests. Concerns over the growing Islamisation of Turkey form the backbone of gloom and doom stories of how the once-loyal ally could now become a “new Iran”.

However the recent protests have also shown that the threat of creeping Islamisation is an important matter for the secular, liberal population of the country too.

Since its foundation, one of the most sensitive issues for the Republic of Turkey has been how to create compatibility between secularism and Islam. Up to 99% of the population of 75m people in Turkey is Muslim. The constitution prohibits discrimination on religious grounds, but also protects the existence and integrity of the secular state, creating one of the deepest fault lines of governance.

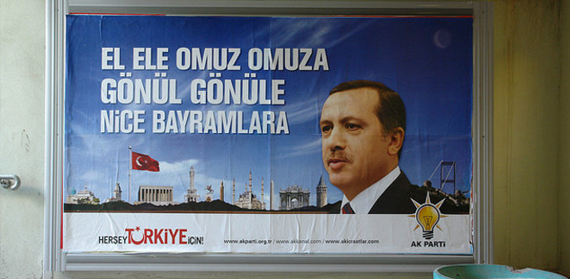

Until recently, the military acted as the guardian of the secular state, and a number of coups d’état – real or virtual – took place in the name of protecting secularism in Turkey. However since the AKP government took power in 2002, the civil-military power balances in the country have changed considerably and now it is hard to know whether the Turkish military could resume its self-appointed guardianship role ever again.

Liberals claim a ‘hidden agenda’

While the influence of Islam in Turkish politics ebbs and flows, and is by no means straightforward, a litany of high-profile issues around secularism has built up “evidence” in the eyes of liberals, supporting their claims that the AKP has a hidden agenda of changing the secular tradition of governance into an increasingly Islamic one.

The controversy about headscarves for women in public space such as schools, universities and official buildings has always been a huge issue. After years of making headlines as one of the top religious freedom issues in human rights reports, the ban at universities has recently been lifted.

Religion in the national education system has, in itself, presented problems. In recent times, some of the biggest issues for secularists have been around the new law which structures education into three four-year segments. Before this, students had to complete eight years of education before being able to attend a religious education high school, however, it is now possible that after the first four years, students could go to middle school or opt for home schooling. Secularist critics perceive this as a ploy for pushing students to pursue intensive religious education at a younger age.

Women’s rights has also proven to be an area of potential conflict between the traditional and the secular in Turkish politics. A draft Bill presented this year would require women wanting an abortion to do so within the first six weeks of pregnancy, rather than within 10 weeks, as the current legislation allows. A law introduced last year prohibiting elective caesarian births – after the rate was found to have doubled to 48% of births – has been seen by secularists as another attempt to interfere with citizens’ private lives.

The final straw has been the new alcohol law, which the government claims is to protect young generations from alcoholism. But among 30 OECD countries, Turkey with 1.4 per litre per person has the lowest alcohol consumption. The legislation has been seen as another move to mobilise the conservative base of AKP before the forthcoming elections.

The government has always argued that their only objective is people’s welfare. These laws are nothing to do with the Islamisation of Turkey and the government has no interest in interfering with people’s private lives. To a large extent, such rhetoric has helped the AKP win elections since 2002 (with nearly 50% of votes in the last general election). This strong showing supports the AKP’s claims that both the prime minister and his party are very popular and according to a recent Pew Research survey, 62% of Turks have a favourable view of Erdoğan.

Breakdown in trust

The recent raft of legislative changes to which secularists have objected has eroded that trust. Now in the minds of many the question is how long “interference” will continue before Turkey becomes a country like Iran?

A contributing factor to this public mistrust is certainly a public relations issue: a lack of a strong opposition and a succession of landslide election victories seem to have created a certain level of over-confidence within government. As a result there have been few public consultations at a time of highly significant legislative change. The AKP needs to show that it is still interested in listening to all voices in the country and as Erdoğan needs to show, as he pointed out recently, that he is the “servant of all” in Turkey.

Fundamentally there seems to be a complete communication failure between the government and secularists and Turkey has become a divided society with many fault lines. Islamists are seen as set against secularists, Sunnis against Alevis and Turks against Kurds. It’s hard to imagine that peace and stability can be assured in such a society.

All stakeholders need to carefully assess what can be done to reconcile deep divisions in the country. Turkey may not be becoming an Islamic Republic but its recent troubles prove that is struggling to deal with diversity and balance its sensitive secular tradition of governance with Islamic religion and culture.

Alpaslan Ozerdem does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Comments are disabled