Boat at Eftalou on the northern coast of Lesvos, with Turkey in the distance. Heaven Crawley

Guest post by Professor Heaven Crawley, Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations and Dr. Nando Sigona, University of Birmingham

It is estimated that in 2015, more than a million people crossed the Mediterranean to Europe in search of safety and a better life. 3,770 are known to have died trying to make this journey during the same period. This so-called “migration crisis” is the largest humanitarian disaster to face Europe since the end of World War II.

That’s why we’ve been working to examine the conditions underpinning this recent migration across, and loss of life in, the Mediterranean.

Our first research brief , based on interviews with 600 people, including 500 refugees, shines a light on the reasons why so many risk everything on the dangerous sea crossing. It also offers an insight into why the EU response has been so ineffective.

One of the main problems with the current approach to this crisis is the assumption that refugees and migrants are drawn towards particular countries because they offer employment, welfare, education or housing. This ignores the fact that in 2015 over 90% of those arriving by sea in Greece came from the world’s top-ten refugee producing countries, 56% from Syria. The ‘migration crisis’ is in fact a crisis of refugee protection.

Of course those who have lost everything want to live somewhere they can rebuild their lives. But the assumption that people are drawn to particular countries presupposes that people know and understand the nuances of asylum policy and practice across a wide range of countries before arriving in the EU.

It is clear from speaking with refugees that those on the move have only partial information about these matters. Decisions about where to go are made ad hoc along the way. More often than not they are based on variables and opportunities that arise on the journey or are communicated to them by agents and smugglers.

Our research suggests politicians will fail in their attempts to stem the flow of refugees if they continue to make assumptions about what drives people into the boats in the first place. Shutting down borders without providing protection, resettlement or humanitarian assistance will not stop people from travelling across the sea, it will simply drive demand for the services of smugglers who can facilitate access and increase the risks for those travelling into and across Europe.

Learning from the past

Our research also suggests that there is a relationship between the decisions made in Europe and deaths at sea.

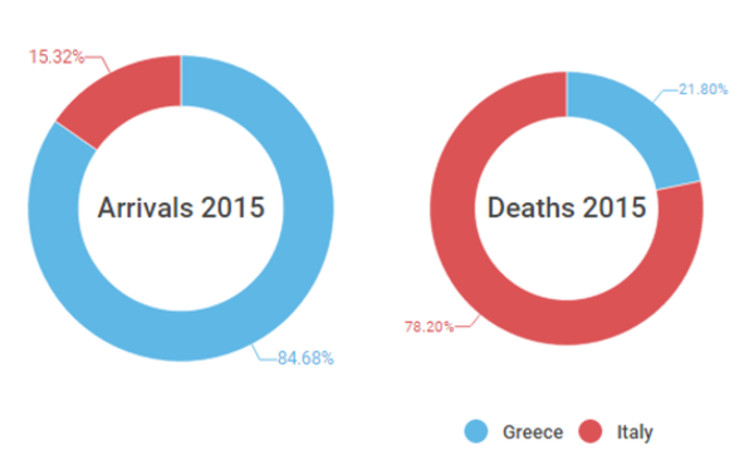

Data shows that 2,892 people died crossing the Mediterranean from Libya in 2015 – one person for every 53 arrivals. Across the Aegean route from Turkey to Greece, the death count for 2015 is significantly lower, both in absolute and relative terms: 806 dead or missing against 845,852 arrivals. That’s one person dead or missing out of every 1,049 arrivals.

Arrivals and deaths by route taken to Europe in 2015

Arrivals and deaths by route taken to Europe in 2015. Data: IOM; Elaboration: www.medmig.info

This can be partly explained by the fact that the crossing between Turkey and the Greek islands – around 10km – is much shorter than the distance between Tripoli and Sicily in Italy, which is around 600km. But it doesn’t explain the very significant variations now seen in the same route. Since the beginning of 2016, the death toll in the Aegean has increased rapidly, with one person dead or missing for every 409 people who arrive safely.

Changing weather conditions may be partly to blame, but there are other factors to consider – most notably border patrols and search and rescue efforts.

Much can be learned from what happened previously in the central Mediterranean route from Libya to Italy. A closer look at deadly incidents there shows that deaths were much higher in the first four months of 2015, with a single incident causing more than 800 victims in April. This pattern was quite different from the one seen in 2014 when just 17 migrants died in the first four months of the year.

The crucial difference between 2014 and 2015 was the reduced presence of search and rescue operations. In 2014, Mare Nostrum, the well-resourced operation led by the Italian navy was still running. This went out into international waters to help boats in trouble. By the end of 2014, Mare Nostrum had been replaced by Triton, a smaller operation, with no mandate to rescue people. This was led by the European border agency Frontex. The decision to end Mare Nostrum was partially fuelled by the assumption that rescuing people at sea would encourage more to make the dangerous sea crossing. Hundreds of people lost their lives as a result of this assumption.

A funeral for 24 people who died in a boat travelling from Libya to Malta. EPA/Lino Arrigo Azzopardi

Following the tragic April incident, Triton was revamped. It was provided with more resources and expanded into rescue missions. This produced an immediate effect on the death toll, which went from an average of 422 deaths per month between January and April 2014, to 150 per month for the rest of the year.

Increased border controls, increased risks

So could a change in the nature of patrols in the short stretch of sea between Turkey and Greece explain the recent increase in death rates seen in the Aegean?

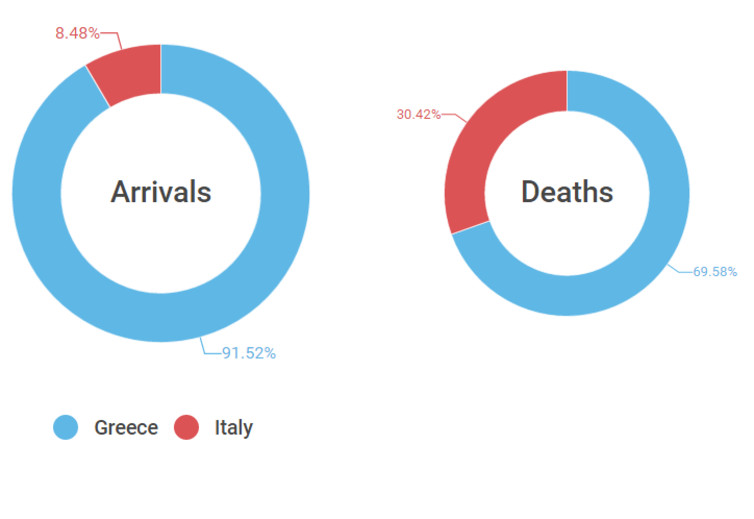

Arrivals and deaths by route taken to Europe in 2016

Deaths and arrivals by route in 2016, to March 24. Data: IOM; Elaboration: www.medmig.info, Author provided

Certainly the period since January 2016 has seen a noticeable change in the way the authorities handle irregular sea crossings. NATO vessels have been brought in and borders patrolled more aggressively. The official policy is now that anyone arriving by sea between Turkey and Greece will be sent back.

Our research suggests the death rate is likely to increase as a result of this approach. The demand – and need – for access to protection continues and, as long as it does, smugglers will simply send their overcrowded boats across the Aegean using different, longer routes to evade the authorities.

Back in October when we were undertaking fieldwork in Lesbos, there were already signs that this was starting to be the case. Boats were being sent across at night, when the chances of detection were lower – but also the chances of rescue.

It also seems likely that other routes will start to open up, or that the use of other more dangerous routes (such as from Libya to Italy) will once again increase. At the moment this is largely speculative, but even a cursory look at the figures suggests that this might already be starting to happen. Between March 10 and 17, there was a 47% decrease in the number of arrivals to Greece but a 518% increase in the number of people who were picked up off the coast of Libya. Only time will tell whether this becomes a trend.

The fact is that the vast majority of people migrating across the Mediterranean to Europe do so because they believe their lives are in danger and that there is no future for them – or their children – in their home countries or the countries through which they have travelled.

The failure of politicians to acknowledge this and to provide alternative ways for refugees to access protection means that many will continue to risk their lives crossing the sea. And that increasing numbers will die trying.

Originally written for ‘the Conversation’.

Comments are disabled