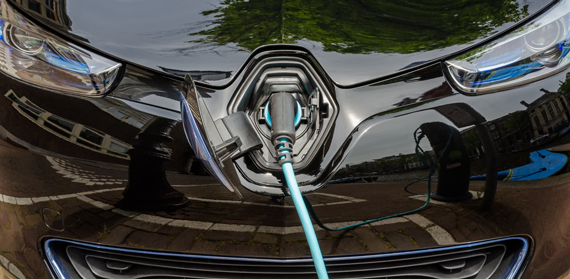

The electric movement/Shutterstock

Guest post by Richard Brooks

For once the hyperbole is justified, the automotive industry is really reaching an ‘unprecedented’ tipping point: carbon emission regulations are forcing carmakers to abandon long-established propulsion technology in favour of electrified powertrains.

This represents an opportunity for new firms and market-entrants to challenge the giants of the industry. In the USA Tesla Motors (founded 2003) has emerged as one of the most identifiable battery electric vehicle (BEV) brands in the business; whilst in China BYD Auto (2003) is now the top selling BEV. Fisker, Detroit Electric, Faraday Futures, even Apple are all new entrants eying up this small but fast growing segment – from the other-side of the Atlantic.

The absence of new brands emerging from Europe is telling, not least because Europe should have been the ideal market for electric powertrains: it enforces tougher fuel emission standards than the US, cars are on average smaller and driving distances shorter. The failure of new European manufacturers, including of those of parts and systems, to capitalise on this opportunity suggests gaps in the wider ‘innovation system’.

For European manufacturers the problem is on the supply-side. As part of a Coventry University study funded by the EC (called INTRASME), over 100 automotive manufacturers and suppliers to BEVs in four locations across the continent were interviewed. It quickly became clear the new-entrants faced considerable barriers to commercialisation.

In seeking to integrate new brands or technologies into established supply-chains small firms need finance to transform costly prototypes into goods that can be mass produced. Multinational car-makers and suppliers demand assurance that new products will have a market, will be price competitive and production can be scaled-up. In such a capital intensive environment, this gap in expectations is tough to bridge.

Electric power points around cities/Shutterstock

Tesla Motors emerged in 2003 out the Californian technology scene and where venture capital investment is famously fluid and there exists a high per capita income market for early adoptions. This is not a context that can be easily replicated and the approach taken by different European regions has been informed by their varied cultural and geographical circumstances.

In regions where the supply-chain is largely foreign owned, such as in the UK’s West Midlands or Poland’s Warsaw, most government and regional measures have focused on increasing demand for electric vehicles, whilst providing R&D funding for niche technology firms. Yet frequently these specialist firms remained small, unable to gain the funding to move beyond low-volume production and (in the West Midlands) operating in relative isolation to prevent loss of intellectual property to peers.

In Piedmont, Italy, the combination of a more domestically-owned supply-chain and a culture of collaboration and networking led to a number of benefits: Major suppliers convene networks to keep track of new innovations, small firms collaborated to share expertise and lower overheads, whilst public authorities opened up procurement processes to encourage new firms to gain first clients.

It was in Bulgaria, however, where the highest level of commercialisation was observed. In other European regions R&D funding is often diffused over a range of technology types, in Bulgaria the government sought to focus on the narrow field of ‘conversions’. By specialising in retrofitting conventionally fuelled vehicles into BEVs, firms were able to develop an immediate route to market and revenue stream which could be re-invested into technological development, rather than starting with it.

These observations point towards several areas of future consideration for policy: The first issue is the relationships between measures to stimulate market adoption and to domestic supply. Emissions policies are potentially an important lever of economic development, but only if the two approaches are mutually reinforcing.

The second observation is that routes to market must be considered. Advances in technology are unlikely to benefit a region, if the surrounding supply-chain is uninterested, or unable to take decisions about investing in these advances. Otherwise technology is often acquired from abroad, as was often observed in the UK.

Finally, strategy and specialisation is important. In Bulgaria retrofitting was championed, whilst in Piedmont small car design and telematics are favoured. Indeed, the lack of a defined specialisation strategy in the UK is perhaps especially noteworthy: when Tesla first sought to break into the US market with a sports car design, it turned towards the UK car-maker Lotus for the body. Perhaps had the UK focused on its established area of strength (in lightweight motorsports) it might have established a better foothold in the now fast growing EV market.

Comments are disabled