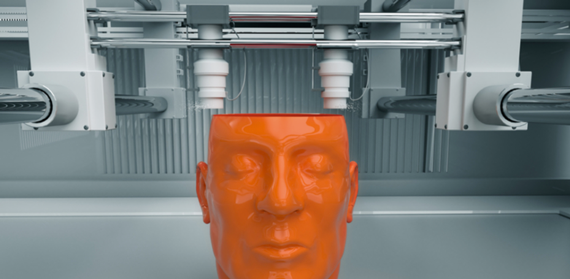

Dabarti CGI

Alan Richards, Disruptive Learning Media Lab

The increasing pace of technological change is obvious. Much sought-after and expensive electronic gadgets are out of date within months of purchase and obsolete a few years later. This shortening of product life-cycle, combined with increasing emphasis on innovation has made fund managers apprehensive. Gone are the days of medium to long-term investments that incurred little risk.

Fund managers are not the preserve of wealthy organisations with profits to reallocate. As developed countries lumber towards state pension crises, the need for citizens to have private income in old age is becoming of paramount importance. Such private financial security relies heavily on the effective utilisation of pension funds and associated products.

Pension funds traditionally have been invested in one of two ways, either through specialist funding of fixed assets to maximise returns, or more often, spread across a wide spectrum of bonds and shares that reduce overall risk.

The content of such funds usually contain fixed assets that include bricks-and-mortor investments in domestic and commercial property. However, as location independent working and the long-since forgotten promise of “telecottaging” has morphed into a practice of working from home or public spaces, the need for large-scale commercial edifices has dwindled outside of London and other major cities.

In addition, a proliferation in online shopping has seen city centres hard hit by high rents and low footfall. These conditions have resulted in less than attractive investment opportunities for those charged with managing our retirement funds.

Investments in tech companies has risen to such an extent that some people are predicting another dotcom bubble due to unrealistic appraisals of social media and app-based start-ups. These elements have combined to provide an uncertain future for traditional investment portfolios as the internet completely redefines human behaviour and spending patterns.

Since the 1990s dotcom bubble and resultant downturn, it has become increasingly difficult to predict complex technologies. And with the advent of blue ocean technologies, for which the market is virgin territory, it has become more of a challenge to model risk.

The near exponential growth of technological development and innovation has seen new markets emerge, rise to prominence and disappear, almost without trace. A mere generation ago, the idea that a majority of the workforce would be engaged in computer-based activity was unthinkable to many. However, now computer-based jobs dominate in developed countries while many traditional jobs in heavy industry have been consigned to history in Europe and beyond.

Age of uncertainty

With such a huge shift in workforce and product, it is little wonder that financial institutions struggle to keep up with the rate of change. The risk models upon which they rely are often based on established paradigms that may no longer hold true. Newer risk models lack the certainty of reliable data gathered over a long period. Thus, risk has increased in line with uncertainty as investment profiles have had to encompass as yet unrealised investment opportunities.

Commercial property: still as safe as houses? Jeremy Reddington

New models must be sought that factor in such mathematical functions as fuzzy logic to integrate uncertainty into the very fabric of risk analysis while being able to make predictions base upon ever-decreasing traditional data sets.

While the time period over which useful data may be collected is decreasing in line with shorter product life-cycles, the ability to gather, collate and disseminate information is growing due to the rise of “big data” and real-time communications technologies that will power an emerging “internet of everything”.

Risky business

As there is an interdependency between innovation and investment, a solution must be sought that allows fund managers to assess risk and allocate financial resources in order to fuel innovation that, in turn, increases wealth generation.

Investor sentiment has been in turmoil in recent times as inflated stockmarket flotations see IPOs that conflate rational financial profiling with value-added elements that contain little more than observer bias. Such short-termism has resulted in large fluctuations in share price for new public companies, thereby reducing their attractiveness to long-term fund managers for whom volatility increases risk to an unmanageable level.

Built-in obsolescence is a major problem for investors. dwphotos

The lack of such a solution has created a gap in the market that has prompted the appearance of “kickstarter” investment models, enabling multiple donors to ascribe small amounts of money to an online account.

Tech company start-ups have used this model widely, but the impact of such an investment strategy reaches much further. Barack Obama’s presidential campaign of 2008 benefited from an online contribution of more than $28m – 90% of which was derived from donations of less than $100. This is increasingly becoming a model for political fundraising.

But models such as this are all about individuals contributing to projects they approve of, rather than from which they hope to derive a return. Such investment alternatives have seen an entirely new market evolve around the small investor. This only serves as further testament to citizens becoming co-creators of innovation projects, news items, art critique and political mobilisation.

Pension funds are the largest investment most people make outside of property, so the need to minimise risk is paramount when managing them. The future of risk assessment may be in question but the need to allocate resources in an effective manner is more important than ever. Therefore, fund managers and the algorithms that support decision making must be capable of modelling risk within a fast-paced and uncertain environment if innovation is to maintain the investment it requires in order to flourish into the future.

Originally written for ‘the Conversation’.

Comments are disabled