Guest post by Professor Sally Dibb and Dr. Helen Roby, Centre for Business in Society and Dr. Jose Cavero (Open University)

Why community energy matters

Global reaction to President Trump’s recent rejection of the Paris Climate Agreement is a timely reminder of the political, economic, and social importance of climate change. Meanwhile, the UK government has published new rules to increase flexibility in the generation, storage and use of electricity. Ministers hope that these regulatory changes will make it easier for individual consumers and communities to benefit from renewable energy. This then, is a useful moment to consider that sustainability and the need for renewables are as relevant to individual consumers as they are to national governments.

Many of us feel disengaged from the climate change debate, so you might be surprised to discover that community energy is a key part of the UK government’s plan for decarbonising the energy sector. Sustainability at the local level is important for several reasons. Community energy is considered by government to cover ‘aspects of collective action to reduce, purchase, manage and generate energy’. They estimate that during the last five years some 5000 community groups have become involved in these initiatives involving energy. Projects range from encouraging energy saving behaviour change; and installing energy saving measures such as roof and wall insulation; to joint purchasing of fuel and energy; the installation of renewable technologies, such as solar panels, ground source heat pumps and wind turbines; and trialling smart technologies in conjunction with industry partners.

Although such initiatives might seem small scale, estimates suggest that these projects could produce up to 14% of installed energy in the UK. Not surprisingly, local energy initiatives are being seen by government as an attractive bottom-up way to tackle climate change. Involving the public in local sustainability initiatives could also offer an effective route to wider behaviour change.

There are, however, many barriers to change that need to be tackled, particularly the low levels of public engagement with the sustainability agenda.

The CAPE project

In a recent study funded by InnovateUK, CBiS researchers worked in partnership with SmartKlub, a smart energy SME, the Satellite Applications Catapult, Tech Mahindra, the Open University, Milton Keynes Council and Community Action MK, to look at what it takes to get communities involved in local energy projects. Although the project was initially based in the Milton Keynes area, the study results are being used to roll the project out to other parts of the country.

The Community Action Platform for Energy project – or CAPE, for short – has developed an interactive website offering a one-stop shop for communities to get involved in local energy projects. CAPE is different from other community energy websites and resources, because it puts Big Data tools in the hands of local people. These tools bring together satellite images and heat maps of local buildings, energy performance and usage data, and sociodemographic information. Using clever algorithms to combine these different data sources means users can find out, for example, how much energy they might generate or how much money they could save on their heating bills by installing solar panels to their rooves or putting ground source heat pumps in their gardens

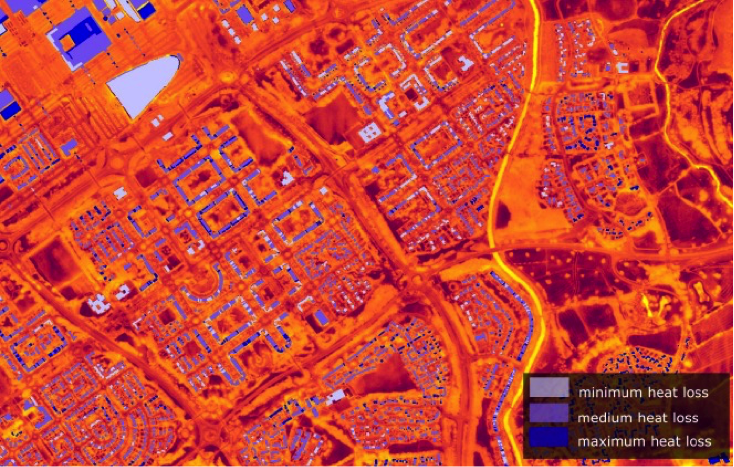

Take a look at the satellite images in Figure 1. In the top image, you can clearly see the heat being lost from local buildings, while on the bottom, the potential for solar panels based on roof area and angle is visible. Such information offers vital insight into what the benefits might be of getting involved in certain kinds of energy projects.

Figure 1 Satellite images

What we learnt

The project shows the role that Big Data can play in supporting community energy projects. Given access to the right tools, designed in the right way, these benefits can be made directly available to regular citizens who want to do their bit to combat climate change.

We also learnt more about the variety of factors which motivate communities to get involved in community energy projects. As you might expect, some are personal and tangible, such as seeking to reduce household energy costs or improve the comfort of their homes. Other motivations are much more socially oriented. Some of these motives focus on tangible outcomes, such as the desire to create work for local tradespeople, or to ease energy bills for local people suffering fuel poverty. Less tangible motivations include wanting to build community identity, or feelings of empowerment arising when the community joins together behind a common goal. Interestingly, the desire to cut carbon is very low down the list of motives, if it features at all.

Local people, we discovered, are more likely to get involved in energy projects when all of the benefits arising from it are retained within the community. As one community leader we spoke to explained:

We’ve used local designers, local web people, we try to stay as local as possible, that’s the whole point, you know. It’s a community benefit, so the community has to benefit and there’s all sorts of ways that it can do that, and the first way is to actually use local people.

We found that communities which are successful in delivering energy projects do not necessarily identify themselves as energy communities. Although some had been established specifically with this aim in mind, others became involved in energy projects after being set up for other reasons. This group ranged from local women’s groups and hobby societies to sports clubs and faith communities. So most of these communities have emerged from local interest, rather than in response to government campaigns. Having inspirational leadership and uniting behind a common goal were important indicators of success.

Each of these communities had been on different journeys in relation to the energy projects they supported. One began by generating income from installing solar panels on the rooves of public buildings and then invested the income to enable local citizens to insulate their drafty Victorian homes. Another was building a community centre, where sustainable design was key to keeping fuel bills low. Understanding these differences, along with the varying contexts and factors which have motivated them is key for policy makers and other stakeholders seeking to improve engagement with community energy.

Reflecting that community energy can lead to a strong sense of community empowerment, we found evidence that success in one project – whether energy-related or not – can trigger interest in other community-based initiatives. For example, project partner Community Action MK has supported a number of successful local-projects, including one to create a network of community energy champions (https://communityactionmk.org/energagemk/). Our research findings serve to reinforce the view that communities have a crucial role to play in what government is referring to as the democratization of energy.

We are delighted that the CAPE project has won a Smart Cities 2017 award in the housing category, recognising the projects ability to improve living standards and support low cost living. These awards recognise best practice in smart city transformation across the UK.

The Smart City UK 2017 Awards are supported by highly regarded bodies such as TechUK and The Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET). To find out more, go to www.smartcityuk.com

Additional Reading

DECC (2014). Community Energy Strategy, Full Report, Crown Copyright. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/275169/20140126Community_Energy_Strategy.pdf

Rae, C., Bradley, F. (2012) Energy autonomy in sustainable communities—A review of key issues, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16.

Walker, G., Hunter, S., Devine-Wright, P., Evans, B., Fay, H. (2007) Harnessing Community Energies: Explaining and Evaluating Community-Based Localism in Renewable Energy Policy in the UK, Global Environmental Politics, 7:2.

Comments are disabled