Free flowing trade across Ireland’s border should not be taken for granted. Niall Carson/PA Archive/PA Images

Guest post by Jason Begley, Centre for Business in Society

You only have to look at the levels of trade and economic development in Ireland over the past century to realise the significance of a smooth border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. The Republic is best described as a small, open economy whose fortunes have been inextricably linked with those of its larger neighbour, the UK. If this holds true for the Republic then it is even more so the case with Northern Ireland.

What is perhaps not appreciated is the comparatively wealthy character of the Irish economy as a whole in the years before independence. In 1913 Ireland ranked tenth in a European league of 23 countries for Gross National Product per capita. The perception of Irish underdevelopment was only relative to industrial pioneers like Britain. While agriculture did dominate, the hallmarks of a modern economy – a strong secondary sector and a growing tertiary sector – were developing fast, driven in part by labour mobility and emigration, but also by technological change, capital investment, access to major markets and a stable currency.

The pattern of its development was uneven, however, with the bulk of heavy industry such as engineering, shipbuilding and textiles located in the North. While, in the South, industry was specialised in food processing located near key ports in Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Waterford.

Division and decline

The island was officially divided in two on May 3 1921 following the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. A land border was created, stretching 310 miles through a patchwork of forests and farms. With the emergence of two separate countries, came two distinct economies.

While the creation of the common travel area in 1923 allowed movement of peoples, over time the border would become a customs and security control that took on social, cultural and political significance. The decision by the then Irish Free State in the early 1930s to industrialise behind a tariff wall served to deepen the economic divide.

Then, the Free State’s neutrality during World War II followed by the declaration of a republic in 1948 further emphasised social and cultural differences between North and South. During this period dwindling southern Irish exports were oriented toward UK markets – more than 90% went to the UK from 1924-1950. Trade in the opposite direction was higher, but during the same years the Northern Irish economy stagnated as traditional industries declined, the fillip of material demand from WWII aside.

By the end of the 1950s, inward-looking economic policies, including tariff protection and restrictions on capital imports, were deemed responsible for the under-performing southern economy. In 1958, the Irish government decided to open up its economy and encourage investment through tax and investment incentives.

This policy shift was matched by a reorientation away from UK markets. Trade with the UK as a whole declined thereafter – export and import shares fell from 74% of the Republic’s trade in 1960 to a little over 30% by 1992. Entry into the European common market (EEC) in 1972 helped accelerate this change.

More importantly its EEC membership, determined largely by the decision of the UK to join, also served to legitimise Irish economic and political concerns as a peripheral economy. The benefits of membership for the Republic were slow to materialise and any gains were negated by the second oil crisis in 1979. To counter the price shock, the government spent vast amounts, leading to enormous public debt and threatened national bankruptcy. This in turn was followed by financial austerity and high unemployment in the 1980s.

Border checks during the troubles slowed things down. PA/PA Wire/PA Images

Across the border, the North’s economy followed a similar pathway. At its creation the then wealthy Ulster province was envisaged as a self-sufficient net contributor to the British revenue. But decades of industrial decline saw these contributions dwindle.

Instead, Northern Ireland required significant government support in the 1960s. Investment grants, tax concessions and other inducements were used to attract foreign investment. However, as the UK entered prolonged recession in the 1970s, these funds dried up and industry suffered. The background music to this was the turmoil of the Troubles, during which cross-order relations and economic activity reached their lowest ebb.

An exceptional recovery

Recovery, when it came, was exceptional. In the South the economy grew at an average of 7% each year from 1987 to 2000. However it is more accurate to see this as compensation for years of under-performance, as one of the poorest countries in the common market began to converge with richer trading partners.

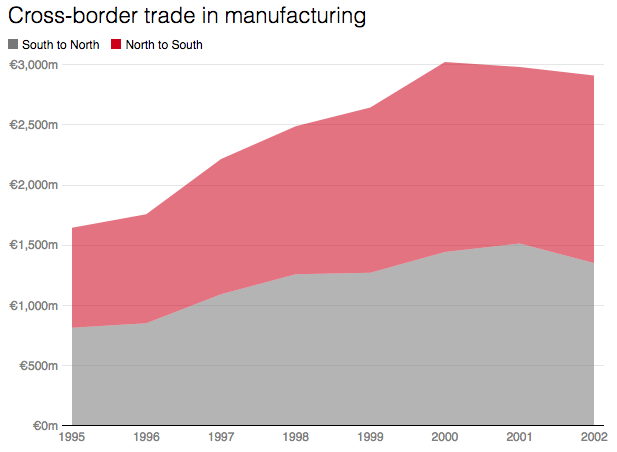

The North’s economy was not unaffected by this development. It also coincided with a detente between the two during this period. Starting with the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985 and then the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, political relations improved and translated into economic gains. Since the early 1990s there has been a steady growth in cross-border activities only partly slowed by the credit crisis of 2007-08.

Source: The Conversation | Data: InterTradeIreland

There have also been increases in tourism, investment and travel. Around 30,000 people cross the border daily for work purposes and approximately 177,000 lorries and 250,000 vans cross each month. Trade is now valued at around £3 billion a year.

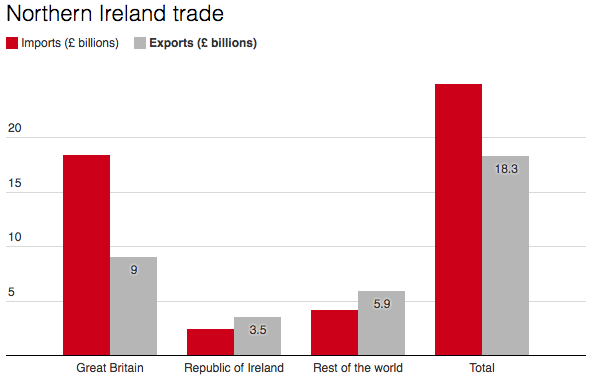

The latest estimates for the Northern Irish balance of trade are more compelling. They identify the Republic as the North’s largest external trading partner.

Source: The Conversation | Data: NISRA

For the 1.81m people in the North and the 4.78m people in the Republic, this cross-border trade is huge. Of particular importance is the agricultural processing industry with supply chains crossing the border several times before final production.

One-third of the total trade between the two economic areas is in animals and food. Under World Trade Organisation rules, tariffs on dairy produce are approximately 30%. Disrupting the sector by forcing businesses to completely rethink their supply chains could prove costly.

After decades of diplomacy and development the two economies of Ireland are more integrated than they have been in a century. The EU was central to this, proving an honest broker in these discussions. Brexit threatens to undo these advances and once again partition the Irish economy. Further, it threatens to undermine the positive relations that so many have worked so hard for, for so long.

Irish politicians, on both sides of the border, must fear a return to a dark period in the history of the island. And Brexit negotiators should be mindful of this as they bash out their divorce settlement.

Comments are disabled