Shutterstock

Guest post by Nandu Devi and Dr. Stella Despoudi, Centre for Business in Society

MM UK, a subsidiary of the Munoz Group, is an important supplier of fruit and flowers to several major UK supermarket retailers. MM’s £20 million 220,000 sq. ft. newly built packing and processing facility at Alconbury Weald Business Campus is an outstanding example of the meticulous application of sustainable and efficient supply chain principles. By ‘keeping it lean’ MM are able to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability which ensures that they are in step with the demands of their customers and they are able to make cost savings which benefit their own business. Yes, sustainability is good for business!!

So, what is meant by ‘lean philosophy’? Supply chain specialists use this term to refer to the elimination of waste of all forms during production so that higher quality can be offered to the customer at lower cost (Slack et al. 2013). The lean approach continuously distinguishes value-adding activities from non-value adding activities by eliminating waste (Antony 2011). Waste can be classified into 7 types: waste from overproduction; waste of waiting time; transportation waste; inventory waste, processing waste; waste of motion and waste from product defects.

Efficient waste management is key to lean production. Recycling and re-using of materials are important practices.

The 7 types of waste are significantly reduced in MM’s operations through the adoption of different lean principles and techniques. First, the organisation of the loading and unloading docks ensures that transportation waste is reduced as product movement only occurs for value-adding activities. The “L/U” shaped compartmentalisation of individual flow space minimises the risk of cross contamination and thus reduces the possibility of waste from product defects. This “L/U” shaped compartmentalisation also drastically reduces space used on the shop floor and thus enables shorter distances between single cells. In this way waiting time waste and waste of workers’ motion are eliminated too.

The allocation of a ‘grey space’ which can be used by either the flower or the fruit flow chain allows for fluctuations in demand. Such fluctuations, which lead to low or high inventory levels, are known as the classical ‘bullwhip effect’ (Slack et al. 2013). MM follows a ‘Just-In-Time’ system whereby products are produced only when they are required by the customer. In this way inventory levels can be tightly controlled in order to eliminate waste from overproduction and inventory waste. MM’s tight relationships with its customers and suppliers ensures that supply can be tightly matched to demand. MM has global supply chains yet is able to procure 80% of its grapes comes from just 10 key suppliers which helps to cut waste from overproduction. Only necessary inventory is held in its UK operations.

The focus on building stronger collaborations with a relatively small pool of suppliers also helps to ensure compliance with stringent environmental standards and certifications. The implementation of such standards can contribute to decreased waste throughout the supply chain (see work on the ‘Green Bullwhip’ by Lee et al. 2014).

The perishable and sensitive nature of the commodity handled coupled with the high-volume production cycle poses significant operational challenges. From a lean continuous flow stance, the use of low-medium speed conveyor integrated with a Marco productivity management system ensures continuous production with minimum processing waste.

The conveyor belt is calibrated to optimise the speed at which high quality flower bouquets can be made.

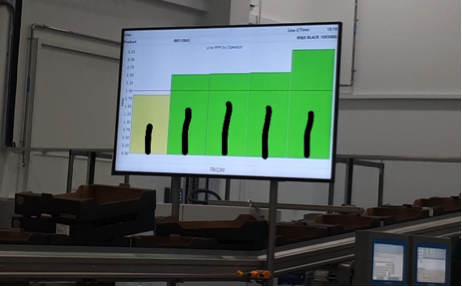

In MM’s operations, lean solutions related to inventory and waiting issues are further extended within the production line. A ‘kanban (Japanese for ‘visual card’) system’ is used to enable efficient movement of the workforce within the operations. Visual control is maintained throughout; in the assembly lines, the digital work allocation and individual load is projected on to a screen so that staff are aware of daily targets and their progress towards meeting them. Similarly, procedures in the event of unpredicted shutdowns are also sketched out on a white board facilitating transparency.

The Marco Productivity system screen, showing the progress of workers towards their targets.

MM’s corporate strategy is interesting as it embraces both a culture of continuous incremental improvements (‘Kaizen’ philosophy) and a culture which is prepared to make radical changes (‘Kaikaku’ philosophy). The firm’s large investment into a new production site geared to lean production principles can be seen as radical but interestingly it has been designed so that changes can be incrementally implemented. For example, current production spaces are sufficiently large to be converted into storage areas if future needs dictate. Furthermore, the roof structure is sufficiently robust to accommodate solar panels if/when such technology becomes financially viable. Future proofing and flexibility are the name of the game.

Overall, MM’s site is a fascinating location for scholars interested in lean production to observe. State of the art practices promoting features such as continuous flow, waste elimination, cost efficiency and value addition are evident. Collectively these indicate that the firm is seeking to implement strong principles of sustainability which benefit the firm’s overall performance by reducing costs and improving product quality.

References

Adams, M., Comber, S. (2013) ‘Knowledge transfer for sustainable innovation: a model for academic-Industry interaction to improve resource efficiency within SME manufacturers’. Journal of Innovation Management, 63–84.

Antony, J. (2011) ‘Six Sigma vs Lean: Some perspectives from leading academics and practitioners’. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 60 (2), 185-190.

Govindan, C.K., Azevedo, S.G., Cruz-Machado, V. (2017) ‘Modelling green and lean supply chains: An eco-efficiency perspective’. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 120, 75-87.

Lee, S., Klassen, S.D., Furlan, A. and Vinelli, A. (2014) ‘The green bullwhip effect: Transferring environmental requirements along the supply chain’. International Journal of Production Economics 156, 39-51.

Slack, N., Brandon-Jones, A., and Johnston, R. (2013) Operations Management. 7th edn. Harrow: Pearson

This blog is part of a short series by members of the Sustainable Production and Consumption Cluster in the Centre for Business in Society. These Blogs were inspired by a visit to the Munoz Group facility near Huntingdon, UK. Munoz supply flowers, grapes, citrus, ice cream and juices into a range of UK retailers. Thanks are due to the Munoz team for the insights they provided into the management of retailer supply chains for fresh produce.

Other related blogs include:

- David Bek, Stella Despoudi and Nora Lanari 2017 ‘Less is More’ in retailer supply chains: what are the impacts on sustainability?

- Lisa Ruetgers and Jordan Lazell 2018 Cutting down waste in the journey from field to shelf: questions of sustainability in retailer supply chains.

- Stella Despoudi, Nora Lanari and David Bek 2018 ‘Can the new era of retailer-led certification schemes shift the sustainability dial?

Comments are disabled