By Dr Eliana Lauretta, Dr Daniel Santamaria, Mr Leitrim Doyle, Centre for Financial and Corporate Integrity

The 2007 financial meltdown and the run-up period leading to the Great Recession are still well-ingrained in our memory and advanced economies continue to pay the price for the extraordinary measures put in place by Governments and Central Banks to recover from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and rescue the financial system from a complete meltdown.

Extensive research blamed financial innovation, such as securitisation and structured financial products, as becoming too complex to understand its risk as an investment vehicle (e.g., Minsky, 1982; Nikolaidi and Stockhammer, 2017; Dafermos, 2018). Moreover, a recent study shows evidence that an overreliance on financial innovation induces financial instability, increases default risk and, ultimately, increases the likelihood of financial crises (Lauretta et al., 2023). However, these studies raise two important questions: 1) what is the role of financial agents’ perceptions of risk in the financial system? 2) How does financial innovation impact what one could label as the perception-belief-behaviour nexus in the context of the financial sector?

Keep an eye on that perception of risk!

In the academic literature, there is little doubt that financial and economic agents’ misperception of financial risk contributed to the GFC. In other words, the mismatch between the sophisticated nature of financial innovation and the agents’ ability to process new information (e.g., see Acharya et al., 2009, Barberis, 2013; Gennaioli, 2015). This gap can be translated into a trade-off between financial agents’ perception of risk (PR) and real risk (RR) operating within the financial industry. It can be defined as an opportunity-cost relationship, loosely described as a type of compensation mechanism.

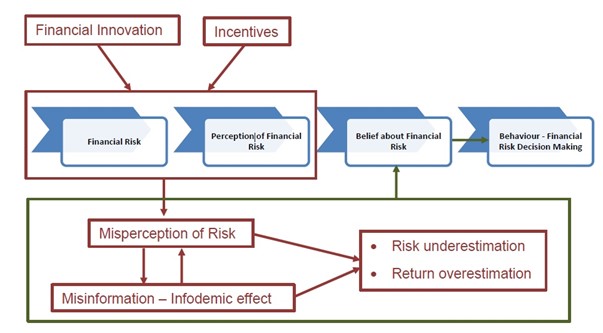

The more financial agents adopt financial innovations, the less they can set rational expectations about risk by increasing the chance of loss. Specifically, the presence of financial innovation together with ‘misaligned incentives’ (Thakor, 2018) can exacerbate the negative trade-off spiral and, as a negative externality, systemic costs are paid by the real economy. However, very little is known about this trade-off so far, and this issue remains unresolved within what we may identify in macroeconomics and finance as the Perception-Belief-Behaviour (PBB) nexus (Figure 1). In response to this shortcoming, the PRiFin project investigates the complex structural and cognitive reasons why financial agents tend to underestimate risk in the presence of financial innovation, particularly in periods of prosperity. (Minsky, 1982).

Figure 1 – PBB nexus in the presence of Financial Innovation and Incentives

The PRiFIN project – Where did it come from?

PRiFin is a pilot project funded by the ASPiRE (Academic Support Programme in Research Excellence) pump-prime research grant scheme at Coventry University in collaboration with the College of Business and Law (CBL) and supported by the Centre for Financial and Corporate Integrity (CFCI).

The PRiFin research team started their investigation from the initial observation that in an era when financial innovations, including FinTech, cloud banking, cryptocurrencies, and Artificial Intelligence (AI), are shaping the future of the global financial system, it has become more crucial than ever to understand the perceptions of risk-taking and risk-seeking in the decision-making process of financial operator’s. This leads to the central assumption of the PRiFin project that financial agents are no longer rational once the role of perceptions dominates their decision-making process, considering the financial innovation speed of “creative destruction.”

To test this assumption four main research questions are tackled:

- How can the PBB nexus be tracked and explained?

- What is the role of financial innovation in affecting the PBB nexus and at what magnitude biased perceptions hamper financial operators’ ability to assess risk?

- How does this nexus impact the creation of negative financial externalities, and increase the likelihood of financial instability, crises, and potential economic downturns?

- What macroprudential actions can policymakers take to minimize distortions taking place within the PBB nexus without affecting market efficiency? [1]

[1] The concept of “market efficiency” refers to the speed at which asset prices are able to reflect all available and relevant market information. Therefore, investors cannot outperform the market and find it difficult (or even impossible) to make speculative movements on financial assets.

Where are we so far? Methodology and preliminary findings at a glance

By means of a multidisciplinary approach that involves finance, economics and psychology, the preliminary findings in the PRiFin pilot study have, thus far, established the existence of the PBB nexus. This exploratory analysis has been done by using an innovative experimental economics-psychology matrix model on a small test sample of 30 finance students. The statistical investigation seems to support the hypothesis of ‘framing effects’ taking place in financial markets. If these results are repeated using financial professionals, we can deduce that financial agents have different levels of engagement with the surrounding environment (i.e., whether this is framed as risk-averse or risk-seeking) and thus, construct different risk attitudes.[1]

Also, it emerges that financial innovation plays a core role in determining financial agents’ preferences in taking up risk despite the financial environment (frame) in which they operate. In other words, it is likely that financial innovation has the embedded characteristics to naturally lower agents’ uncertainty expectations, indistinctively whether the market framework is risk-seeking or risk-averse. Moreover, the initial outcomes show that financial innovation generates cognitive bias[2] (Barnes, 1984) when the financial market presents a risk-seeking attitude and a cognitive dissonance[3] (Barberis, 2013) in the presence of risk-aversion. This is because of the ‘speed gap’ between introducing financial innovations in the financial market and the constraints imposed on agents to process the flow of information about financial innovation.

Therefore, on closer inspection, statistics provide signs of a trade-off between financial agents’ PR and RR operating within the financial industry. Moreover, financial innovation combined with incentives seems to cause misplaced beliefs, and infodemic effects take place in the financial markets. However, a note of caution is required here about the above-mentioned evidence as further investigation is necessary to test its validity.

[1] Two different types of risk attitudes seem to co-exist: the market risk attitude and the individual risk attitude of each financial operator.

[2] Cognitive bias refers to the individual’s deviation from rational thinking.

[3] Cognitive dissonance refers to the individual’s actions misaligning or conflicting with personal beliefs, attitudes or values, leading to stress and discomfort.

What next?

The preliminary findings from this pilot study warrant further research into the PBB dynamics relating to financial risk in the presence of financial innovation. This means upscaling the current research project and generating a more sophisticated and robust empirical analysis to include a cross-country sample of financial services industry practitioners. The PRiFin project has so far raised awareness around this topic and its related issues among financial stakeholders, policymakers and academics. In raising awareness, this pilot study lays the foundations of a multidisciplinary debate on the topic. The work aims to generate fresh insights and encourage further connections and research collaborations across the research community on this ground-breaking topic.

The decision to upscale the project opens an opportunity for the PRiFin research team to work with a larger sample of industry professionals and practitioners. The project will provide the basis for a new approach to developing innovative policy tools and strategies aimed at improving macroprudential policymaking. This can be achieved by embedding instruments that specifically tackle risk misperception and misinformation in financial markets. Our initial results point out the need to look at different policy measures that adapt to different market frameworks and target agents’ cognitive bias (for a risk-seeking market) and cognitive dissonance (for a risk-averse market). Finally, policy actions should be investigated to tackle resistance and obstacles towards fostering and maintaining a healthy risk-averse financial market environment.

References

Barberis, N. C. (2013) Psychology and the financial crisis of 2007–2008. in financial innovation: too much or too little?, edited by Michael Haliassos, 15–28. London: The MIT Press.

Barnes Jr, J. H. (1984). Cognitive biases and their impact on strategic planning. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 129-137.

Dafermos, Y. (2018). Debt cycles, instability and fiscal rules: A Godley-Minsky synthesis. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(2), 1277–1313.

Minsky, H. P. 1982. Can it happen again? a reprise, Challenge, vol. 25, no. 3, 5-13.

Nikolaidi, M., and Stockhammer, E. (2017). Minsky models: A structured survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 31(5), 1304–1331.

PRiFin Research Project Report. (2023). PRiFin: Perception of Risk in the Financial System. CFCI webpage.

Lauretta, E., Chaudhry, S. M. and Santamaria, D. (2022). Unveiling the black swan of the finance‐growth Nexus: Assumptions and preliminary evidence of virtuous and unvirtuous cycles. International Journal of Finance and Economics.

Acharya, V. V., Pedersen, L. Philippon, T. and Richardson M., (2009). Regulating systemic risk. In V. V. Acharya and M. Richardson, eds., Restoring Financial Stability: How to Repair a Failed System, Chapter 13. John Wiley & Sons.

Gennaioli, N., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R. (2015). Neglected risks: The psychology of financial crises. The American Economic Review, 105(5): 310-314.

Thakor, A. V. (2018). Post-crisis regulatory reform in banking: Address insolvency risk, not illiquidity!. Journal of Financial Stability, 37, 107-111.

Additional material

Comments are disabled