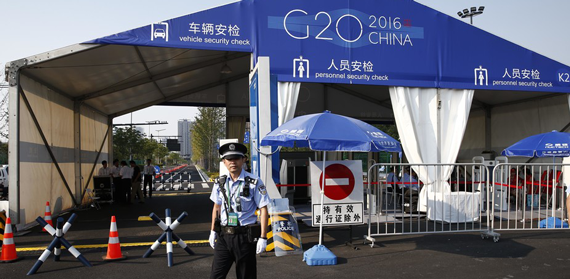

Welcome to Hangzhou. EPA/Rolex Dela Pena

Guest post by Professor Neil Renwick

As the leaders of the world’s 19 biggest economies and the European Union meet in the beautiful southern Chinese city of Hangzhou for the culmination of China’s year at the helm of the G20, it pays to ask exactly what they’re doing – and why it matters.

Yes, the G20 really does matter, and for a whole fistful of reasons. The most important is that, even though the group has expanded its agenda and activities dramatically since its inception in 2009, it remains an informal group, with all the flexibility and ease that implies. The world’s pressurised governments badly need a forum like this, one in which they can hammer out practical measures for collective action with some room to manoeuvre.

The signs are that it’s slowly paying off. Even as the G20 struggles to adapt its agenda to the continuing challenges of slow and uneven growth, it’s also showing signs of real movement on bigger things, striking out in new directions on international development and climate change and introducing new practical initiatives – such as the proposed anti-corruption centre – to make global systems work more effectively.

Hangzhou 2016 is essentially about consensus-building, establishing a workable middle way that can oil the wheels of the world’s crowded and complex financial and economic systems. To make effective policies and put them into practice, governments and international organisations have to negotiate agreement and authorisation among a dizzying array of national and international institutions, to say nothing of electorates.

A new path

There’s a great deal resting on this year’s summit, which could do a lot to recalibrate the G20’s overall sense of direction and priorities.

The official theme of the summit is “Building an innovative, invigorated, interconnected and inclusive world economy”. Within that, there are four priorities: “breaking a new path for growth”, “more effective and efficient global economic and financial governance”, “robust international trade and investment”, and “inclusive and interconnected development”.

In a nutshell, the meeting is concerned with stressing the importance of technological innovation, especially by promoting the digital economy, entrepreneurship and improved financial and economic governance through institutional reforms. But deeper than this, a big priority is to get the group’s members back to medium and long-term strategic planning, rather than on-the-hoof crisis response.

There’s also the imperative to bring developing countries, especially African states, into the centre of global financial and economic deliberations and planning, as well as to produce G20 action plans for both the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement.

Quite a programme to get through. So what’s missing?

Ready to roll. EPA/Rolex Dela Pena

The most glaring gap is what this all means for the G20 itself, which needs to improve both its organisational development and its ability to deliver on its aims and priorities. China has been explicit about its own stance here: as the foreign minister, Wang Yi, put it:

We want to facilitate G20’s transition from a crisis-response mechanism to one focusing on long-term governance so as to better lead world economic growth and international economic cooperation.

Another question altogether is what “an inclusive world economy” would actually look like. This is as much an opportunity as a challenge: the G20 has never managed to shake off its image as a rich states’ club, and if it comes up with a meaningful definition of “inclusive” and actual plans and tools to make the world more so, perhaps the rest of the international community will start warming to it.

This is where China’s year of G20 leadership has already made a positive difference. It has moved sustainable development into the political centre ground and set the goal of coming up with real plans for implementing massive global agreements. It has enforced a mindset of actually getting things done, for example by setting up an innovative economic indicator system for structural reforms and proposing the new anti-corruption measures.

Whether these things can really help the G20 take charge of the global order remains to be seen, but China has laid the groundwork for meaningful action as no G20 leader state ever has before. Soon we’ll find out what the world makes of it all.

Originally written for ‘the Conversation’.

Comments are disabled