University Mental Health Day is a day dedicated to discussing and raising awareness of Mental Health and support the University can provide to anyone who feels they need it. This year, we were lucky to speak to a former student who’s work is inspired by his experiences.

Artist Andy Farr graduated with an MA in Painting in 2017 and returned to the University to exhibit his latest collection of paintings at the Lanchester Gallery. The exhibit “The Twisted Rose and Other Lives” evolved directly from his work during his times as an art student.

We sat down with Andy to talk about his work relating to Mental Health.

This isn’t your first collection of paintings in relation to mental health, what or who inspires your work?

The Twisted Rose project evolved out of the work I did for my MA. I used the MA as an opportunity to look back and try to make sense of events from my own childhood. My father was bipolar, and it is only recently that I’ve come to realise how profoundly his illness impacted my own being. I found that process to be cathartic personally but also that the works resonated with others who had had direct experience of mental issues.

What is the symbolism behind “The Twisted Rose”?

“Twisted Rose” was inspired by “Mac’s” story. He suffered childhood abuse in Ireland. During his therapy he described himself as feeling like “A twisted rose, growing out of the dark into the light, but still carrying the scars of his past”. I chose this metaphor as the title for the exhibition as it seems to sum up much about PTSD and recovery. The past cannot be undone or erased from the memory, but it is possible for people can learn to accept and give meaning to their experiences, and ultimately start to recover and grow.

How did the project and paintings come to life?

The idea of working with people who have experienced PTSD came from Gary Winslip one of the lecturers at the IMH (Institute of Mental Health) in Nottingham. He connected the dots between the earlier project I’d done commemorating WW1 and my interest in mental health. One of the legacies of that War was many hundreds of thousands left suffering from with what was then called “shell shock”, what we now term post-traumatic stress disorder. With the promise of exhibition space from the IMH, Coventry University and Lancashire County Council I was able to secure a second grant from the Arts Council.

When meeting with the painting subjects, how did you approach their life stories and the trauma they had experienced?

For this project my process has had to change radically. Each painting has to be created in a way that respects the feelings and vulnerabilities of the subject. The start point has been a dialogue with the person whose experience I’m conveying. That discussion is focussed on how the emotions and feelings that their experience has evoked rather than the details of the traumatic event. In some cases the conversation took place over several months via email, in others we met face to face quite quickly. Throughout this dialogue I’m looking for metaphors that will act as ways of expressing the experience. From there my usual process of seeking images, colours, textures starts to take over. For several of the paintings the person has agreed to be photographed and the resultant image could be described as a “narrative portrait”. This final step of being present in a painting, and then being in public, is a significant one and so far proved to be cathartic for those involved.

Did this project push you and your work as you were creating a visualisation of someone’s personal trauma and recovery?

Unlike other paintings the degree of responsibility felt by me, the artist, to the person I’m painting is huge. I have never felt the same level of trepidation, as I have during this project, when sending or showing the first version of a painting to someone before. So far the responses have not just been positive but deeply moving as well. This feedback from Rachel, one of the first people I worked with, gave me confidence that the work could have a positive impact on the people directly involved in the project. I’m actually speechless. I cried! The colours are perfect. Me, looking round the corner completely sums up that feeling of lost in the grey world feeling frightened of everything. Welcoming Rachel is the old me too. It’s like you looked in my head and painted. It’s honestly amazing.”

This year the theme of University Mental Health Day is, Using Your Voice. What role do you think the arts can play to help people express themselves?

My own traumatic experiences were much less severe than those who have suffered abuse or been involved in conflict, nonetheless they had a profound impact on my life. Three years ago, I started an MA in painting and this was an opportunity for me to “talk” about what had happened. I realised that sharing those memories through my art was a cathartic process for me. Dr Stephen Joseph says “we human beings are story tellers. Trauma triggers within us the need to tell stories to make sense of what has happened. Books, songs, poetry and art can provide us with the “language” to capture what we are experiencing. It is in the struggle to make sense of a traumatic event that recovery and growth happen”.

People with PTSD often find it easier to talk about the other problems that go along with it – the sleep problems, flashbacks, depression, substance abuse, self-harming et cetera – rather than the real causes. From my own experience I believe that Art is one way to break down some of these barriers. With the help of the Institute of Mental Health in Nottingham I was able to contact people who have experienced post-traumatic stress and create this series of paintings that brings to life their experiences. I have worked with accounts of trauma from a wide spectrum of sources: abuse, birth, accident and conflict etc. Most of the paintings are based on the accounts that people have shared directly with me in order to understand their experiences.

One of the most important things I have learnt through talking to people is that it is possible for people to recover and grow as a result of their experiences – finding new meaning and purpose in their lives. I think like many others, I believed that the psychological havoc caused by PTS inevitably scars for life. Trauma is not an illness that can be cured by a doctor, but by talking – to friends, family and in some cases with the help of therapists, people can learn to accept and give new perspectives to their experiences.

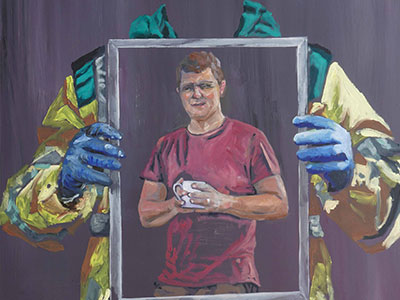

One of the people I worked with was Adam, a paramedic. Initially he was reluctant to share his experience. However, after meeting with him, he agreed to be “in” his painting. By taking he step of being public about his own mental health Adam has become more militant, as he says:

“I believe a bi-product of being in the Emergency Services is exposure to trauma which in turn may lead to mental health. I have had too many friends, crewmates and colleagues both on the service and in my home life take their own lives for often reasons unknown. People who you wouldn’t think had Mental Health problems, who appeared outwardly confident but mentally must have struggled with no support. I don’t want to see that happen to anyone again and I’m hoping by myself speaking out will encourage others to do so also.”