PA/Isabel Infantes

Guest post by Dr. Chris Shannahan, Centre for Trust, Peace & Social Relations

Gallons of ink have already been spilt celebrating or mourning the UK’s decision to leave the European Union. As the dust begins to settle on the referendum campaign, the nation appears fractured. In such uncertain times neighbours seem to have become strangers. How can we heal a fractured Britain?

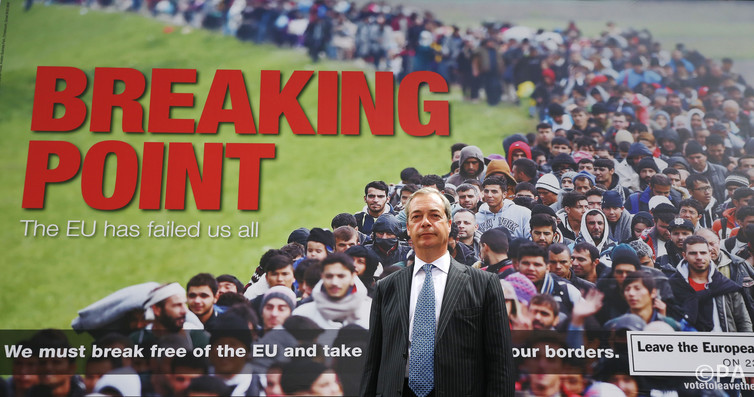

The now infamous “breaking point” poster unveiled by UKIP during the referendum campaign was eerily similar to Nazi propaganda posters from the 1930s. The poster depicted refugees gathering at the Slovenian border – not anywhere near the UK – but increasingly myths trump facts.

The perception was what mattered. “They” are taking over. This poisonous narrative ran through the referendum, giving legitimacy to racism. Travel writer Mike Carter recently walked from Liverpool to London, encountering a sense of abandonment wherever he went. People had no time for politicians but mostly blamed immigrants for their pain. Can we really say Brexit was all about poverty, though, when some of the poorest boroughs of London voted Remain?.

The practice of scapegoating has run through human history like a grubby thread. Think of Shakespeare’s Shylock or the Nazi justification for the Holocaust. In his ‘clash of civilisations’ thesis the late Samuel Huntington argues that “the West” and “Islamic civilisation” are incompatible.

The rash of racist incidents is part of this pattern and since the EU referendum has been legitimised by Brexit. Cards reading “no more Polish vermin” were even found in one English town, evoking memories of the “No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish” signs found in so many pubs and guest houses in the 1950s.

Difference, fear and nostalgia

Where does this demonising of difference come from? The British sociologist Paul Gilroy suggests that a social schizophrenia simmers under the surface in the UK. It is partially a society that is comfortable with its diversity but, at the same time, it’s a nation that resents black and Asian Britons. This is not new but increasingly white migrants from the EU have also been the target for abuse, during the referendum campaign and at the Euro 2016 football championships. Such demonising of the “stranger” reflects the centuries-old practice of scapegoating.

In light of this fear of change, nostalgia for an imagined past and keenness to blame the stranger, we should not be surprised by a 57% rise in reported hate crimes since the Brexit vote.

Farage in front of his poster. PA

It’s tempting to hide under the duvet but now is the time for people from all communities to stand tall against racism, wherever it is found: from snide behind-the-hand remarks to violent street attacks.

Faith leaders from all religious traditions have united in condemning the unleashing of violent racism in the aftermath of the Brexit vote. There is much to be learned from them about living in a diverse society and building inclusive communities. I would suggest that faith can play an important role in building just and inclusive communities.

Welcoming the ‘stranger’

The command to “love your neighbour” is one of the best known phrases in the Bible. However the more radical commandment to “love the stranger, for you were once strangers in Egypt” is found not just once or twice in the Hebrew and Christian scriptures, but 37 times. Similar sentiments are expressed in the Qur’an: “Those who give asylum and aid are in very truth the believers”. In the face of the Brexit backlash, welcoming those whom society frames as strangers can challenge us to see ourselves and each other in a new and more human way. This might sound a bit distant from everyday life but it can mean very practical things like sending our Muslim neighbours Eid cards, challenging racist comments at work or becoming involved in projects such as Restore, which trains volunteers to befriend asylum seekers.

The Sikh idea of the langar can teach us a lot. In this community kitchen all people who visit a temple are offered a free meal whenever they are hungry. This act of unconditional hospitality subverts the divisions of “us” and “them” and paints a picture of our interconnectedness.

When, in May 2013, the extreme right-wing group the English Defence league mounted a demonstration outside a mosque in York, the people praying inside sent them out cups of tea.

When we offer hospitality, we acknowledge the humanity and worth of the person before us. The growing Place of Welcome movement encourages community buildings and places of worship to open their doors to welcome neighbour and stranger alike. Hospitality can begin to subvert the culture of fear that has been unleashed by the referendum. In Birmingham a love your neighbour event outside the Council House encouraged people to “do something kind today”.

The recently murdered Labour MP Jo Cox remarked: “what we have in common is far greater than that which divides us”. This affirmation of interconnectedness echoes the assertion within Islam and Christianity that while we talk and dress and pray in many different ways we are “one body”.

In the fragile world that Brexit has visited on us, this affirmation of our diverse unity provide hope and encouragement for those who seek to assert solidarity. It is only such an affirmation that can defeat the culture of racism that Brexit has legitimised.

Originally written for ‘the Conversation’.

Comments are disabled